Recently I had an interesting conversation over on the Psi-Wars discord. It started with my statement that I didn’t want to see players “saving up” to buy better force swords, that I didn’t want them buying “better force swords” at all. This triggered an entire conversation on gear, RPG genre, and the reasons gear is treated the way it is in RPGs.

I’ve found myself pondering the topic a lot lately, especially in light of people requesting revisions to Psi-Wars’ templates, to update them, and my increasing dissatisfaction with how gear is handled in Psi-Wars. Why do we have gear in games? What purpose does it serve? And what can we replace it with?

What is “Gear?”

Before we go on, we should define some terms. Gear is fairly obvious in GURPS: it’s stuff you buy with your money! I’m talking about “loot” in Dungeon Fantasy, or any equipment that you can pick up and discard. It’s anything that enhances your character that he doesn’t pay for with points, really. It’s an important distinction, for reasons we’ll get back to (or may well become obvious over my meandering musings).

GURPS seems to have inherited its concepts for gear from D&D and the other games of the early era of RPGs. This includes a starting budget for your character, a big shopping list in the book that you’re expected to pore over for hours to find exactly the right gear, encumbrance to prevent you from carrying too much gear (thus, creating a decision matrix of effectiveness within a given monetary and weight budget), and scaling levels of effectiveness whereby the game assumes you’ll give up your starting gear for better gear “later on.”

These are the concepts I wish to discuss here.

Why Gear? Resource Management

Have you ever been playing an RPG, and wanted to use a particular piece of gear, and your GM says “Is it on your sheet?” That seems to be gear-as-logistics. A lot of early RPGs seemed to focus on preparedness: a clever player anticipated his characters’ needs and planned accordingly. For example, we often hear the common wisdom from D&D veterans to “always carry flasks of flaming oil and a 10-foot pole.” The idea here is that you’ll almost always need these items and so you’d be a fool not to carry them. This also means that if you didn’t explicitly write them on your sheet, you couldn’t use them later when you needed them. This sort of thinking encouraged a very deep look at the available gear and carefully articulating every item your character carried.

Depending on your genre, this may be a feature rather than a bug. The most obvious example of this is GURPS After the End, where you’ll count every single bullet your character has. This sort of gameplay creates interesting choices. For example, if you have 6 bullets and you’re fighting 3 zombies, do you use your bullets on them? Maybe you’ll need those bullets more later, so maybe it’s better to risk being zombie-bit by attacking the zombies with your machete. Or, if your group passes by an old ruin, do you want to stop and risk exploring the ruin, hoping for more precious bullets (or whatever else you need)?

The point of the game is to limit what gear you have, and to very precisely know what you have and what you need, and to keep you from easily having everything you need. In addition to worrying about tactical decisions or social decisions, the game encourages you to make logistical decisions. For example, we could go explore that ruin, but if it’s out of your way, that introduces additional travel time, do you have the supplies for that? If you do go and you find a great haul, do you have the room to take it with you, or will it just slow your group down? What if something bad happens, like someone gets zombie-bit, do you have enough first aid kids or anti-zombie serum to fix it? And, on the other hand, if you don’t have these things, maybe you need to go, just for the chance to get the things you need. This adds a new layer of thought and approach to the game. Characters begin to invest in skills like Freight Handling (or higher Lifting ST) to carry more stuff, like other characters invest in survival skills or improvisation techniques so they get more use out of what’s on hand, or traits that prevent the need for any of this in the first place (like higher HT or better Hiking skills).

Early incarnations of D&D definitely had this sort of thing, and often played a bit like a resource management game. Sure, you could attack those monsters, but how many healing potions do you still have? Even the way the spells work fit into this sort of resource management: you had to think ahead to what sort of spells you needed for the day, and you had only a limited amount, so if you have a single “Nuke’m!” spell, did you use it in this fight, or did you save it, in case another, more dangerous fight came up? “Hex crawling,” or traveling across the overland map, also involved a lot of the same logistical thinking of a typical After the End game.

Many RPGs import D&D’s ideas without thinking about them, though, and this creates something of a bug in many games, the “nitpicky” GM who complains that if it’s not on your sheet, you can’t use it. This is fine in certain genres, but can be very out of place in others. Classic examples include your typical Supers game, Pulp adventure, Urban Fantasy, or works like GURPS Monster Hunters or GURPS Action (which even discusses how to handle this with the “Beans, Bullets and Batteries” sidebar). For example, if your band of intrepid explorers dive into the Congo to stop Doctor Demento from completing his death ray, after their fight with the Dread White Apes of Solomon’s Mines, it might be out of place to check to see if the characters have sufficient supplies for the day, if they noted “tent” on their character sheet, and to ask them to roll HT vs malaria.

Why Gear? Gear as the Alternate Experience Track.

The Resource Management aspect of RPGs have fallen out of fashion in many games, and for good reason (mainly when it’s not appropriate to the genre), and later incarnations of D&D have either removed it entirely or streamlined it (“Worrying about the number of health potions and spell slots: yes. Worrying about supplies: no.”), though I think the Old School Renaissance is rediscovering what made D&D’s early logistics ideas so interesting in the first place.

Even so, D&D retains gear and loot as a major element of the game. Indeed, loot has become a byword in video games, especially in the looter-shooter or the ARPG. So even as interest in resource management dwindles (to the point where many RPGs will just restore your HP between fights, and we don’t even worry about finding health packs in modern shooters anymore), they still have gear. Why?

I think we have to understand progression as a concept to understand gear. Players like the skinner-box reward of “play game, get cool toy.” The default toy in most RPGs is the character advancement: play the game, get an XP reward, gain level, get new character feature to play with. However, character progression is slow, permanent and under the direct control of the player. That is, it will take you several “dungeons” to gain a level, once you do, the feature you gain is a permanent aspect of your character, and you’ve not only picked it out yourself, but you picked it out probably when you designed your character (“Great! Finally level 10 and I can take that one feat to finish my combo!”).

Gear, by contrast, is quick, modular and GM-controlled. It may take you three dungeons to gain a level, but you’ll get some sort of gear reward at least once per dungeon and often several times per dungeon (especially as you explore). The gear will often be the result of a randomized loot table, so you don’t now what you get until you pop open a chest or kill a monster and watch him burst like a loot pinata. Finally, you can swap out one set of gear for another. Have a magical ice sword that freezes opponents on a crit and find a magical flame sword that deals extra damage per hit? You can swap it out right away and change you character’s “ice” theme for a “fire” theme immediately. Better yet, you might be able to keep both weapons, and use them as needed, depending on the nature of the fight before you, provided your encumbrance (and whatever other limitations the GM might create, like “No more than 3 magical items”) can handle it. This means well-handled gear creates a second layer of gameplay and choices.

You’ll also collect currency during your adventures which you can use to buy specific gear you want. If your character does have an “ice theme,” and you want that nice set of ice armor or an ice spell from the local magic shop, you’ll accumulate money until you have it, selling off whatever loot and gear that you feel doesn’t suit your character or concept. This reward does not necessarily sync with your experience rewards (you might be able to afford your new item before you reach your next level), which means you can get “neat character tricks” more often than the XP track specifically allows.

All of this assumes that characters shouldn’t start with their preferred gear, and that they’ll find better gear as they go on. This means characters should be willing to discard their father’s lightsaber at the drop of a hat if they find something better. In many genres, like more mythical fantasy or supers, gear defines a character, like a god’s panoply: King Arthur uses Excalibur; Thor wields his hammer; Captain America has his shield. This can change, but it does so as a result of a major character growth or some fundamental change, such as Thor losing his hammer and his eye and needing to quest for a suitable replacement. If we introduce gear-as-alternate-experience-track, we invalidate this. Such a mechanic assumes that our supers can and will regularly stumble across new, superior gear: imagine Captain America finding a magical sword and discarding his shield, and then finding Chitauri armor and ditching his costume for it.

It also puts a great deal of emphasis on gear. Outside of a few, very rare magical items, most characters in the kung fu genre aren’t defined by their gear, but by their skills. A great kung fu warrior is not great because he has The Hammer of the Gods, but because he’s mastered Infinite Hammers Technique, and Buddha’s Palm, and so on. Sometimes, we don’t want an alternate experience track: we want only the one track or, if we want alternate tracks, we want different sorts of tracks (“Martial arts techniques as loot”). In such a case, weapons and armor tend to be largely irrelevant: sure, your opponents carry swords or guns, but they’re no better than your own and your real power rests in your skills.

Why Not Gear?

This brings us back to my discussion of why I didn’t see gear as central to Psi-Wars. Many games and genres don’t make gear especially important, for a variety of reasons.

Gear as Background

In a variety of genres, especially classic horror, soap operas, murder mysteries, or political intrigue games, gear makes no real impact on the game itself. One’s station and wealth might impact one’s ability to access really good stuff (an especially beautiful dress, or higher end monster-slaying gear), but the game generally won’t turn on these, and what gear your character can access, pretty much anyone else can access, and if you need it, you spend a little bit of downtime to get it.

For example, if the PCs in a horror game realize that the local church is haunted by some monster and they want to fight it, they can then go to a gunstore to pick up guns, and then go into the church to fight the beastie, where they’ll probably find out the gun is irrelevant anyway. Another example might be a kung fu game, where characters might have swords or staves, but if they lose their sword, they can grab another sword and fight with it perfectly fine, or grab a mop and use it as an improvised staff without a catastrophic loss of damage output.

These games have gear, but the gear is mostly a background element. GURPS games tend to tackle this by allowing the player to purchase gear out of a budget of 20% of their starting wealth, and then the rest is tied up in “background things.” The character needn’t note that they have a car, or that they have clothes, or that they have cooking utensils in their kitchen, so long as when they need them, the gear that they declare is reasonable for their level of wealth (poverty stricken characters might have a car, but it’s not going to be a Maserati). This prevents the “nitpicky GM” situation, and it de-emphasizes the importance of gear, so that the players can get to “what really matters” for their particular genre, rather than poring endlessly over gear lists. Such games almost never feature looting, because nothing the characters can get from the fallen really matters much to their goals.

Gear as Character Signature

Many characters define themselves by their gear. James Bond wears his suits, Iron Man has his armor, King Arthur has Excalibur. The characters have gear, and it matters a great deal, but it tends to be an extension of their character and that character’s themes. We could think of them as powers that the characters happens to hold, rather than powers that the character has integral to themselves: Iron Man’s powers are his armor, King Arthur’s kingship is symbolized in his sword, etc.

GURPS tends to handle this approach either as gear-as-powers or, more commonly, as signature gear. The character has gear, and likely put a great deal of time into working out that gear, but he typically only does this fora handful of pieces that matter very much to him. If a GURPS player wanted to work out his own character inspired by Iron Man, he might put as much time into designing the armor as he does into designing the rest of his character, but he’s not also going to dive into a gear catalog to work out what sort of car he drives, what sort of guns he carries, and make agonizing decisions over how many rations he should have on his person.

Game genres that feature this approach to gear, typically “mythic” or “heroic” fantasy, or supers, also tend to discourage looting or “upgrading” ones gear. It does this, first, by requiring a character investment into their gear: you pay points for what you have, and so you’re not going to discard it quickly. Also, by genre conventions, you’re paying points for something you generally cannot access any other way. Iron Man can’t go to walmart and buy a better battlesuit, and King Arthur can’t ask a local blacksmith to forge a better sword. As a general rule, if a GM allows a player to purchase, for example, a magical sword as signature gear, he should not then begin handing out superior magic weapons as loot! Or, alternatively, if the player knows that there will be magical loot in the game, then he should also understand it’s likely not worth his points to take a basic, unmagical broadsword as signature gear.

Gear as Narrative Device

Most people don’t think of gear in this way, but it often defines a setting or an adventure without being central to the players in the same way that it might be in gear-centric games. Such gear tends to either be setting defining or a macguffin. Examples of the former are ultra-tech, while examples of the latter tend to be setting-defining pieces that shapes the narrative based on who holds it.

Ultra-Tech gear, or ubiquitous magical gear, tends to change the way the players can interface with the setting. A good example of this might be the Resleeving technology of Altered Carbon. It opens up the opportunity to think of your whole body as “gear,” and it changes how you interact with the setting, but while one might fuss over their sleeve, they’re unlikely to fuss over the technology itself. Its presence allows for new gaming options and new gameplay mechanics, but it itself is not the focus of player-driven choices.

(Incidentally, poorly handled gear in game can sometimes create this sort of gameplay as an emergent property. For example, if a GM allows players to acquire weapons with “save or die” mechanics on them, and then introduces items that armor characters against save-or-die mechanics, and these begin to proliferate out of control, you may get a setting where Save-or-Die mechanics matter more than damage mechanics and characters run around with their magic Save-or-Die swords one-shotting dragons, etc. Such a “mistake” can fundamentally change how players interact with a setting and, if handled well, might create a memorable change).

As a narrative device, a macguffin is better explored elsewhere and commonly known, thus I only note it to highlight its presence as, technically, gear. It may be worth realizing that if the GM accidentally introduces a ridiculous OP item (such as a ring of wishing), one way you can handle it is to acknowledge what you’ve introduced and begin treating it as a macguffin and the center of the story. (ie, suddenly everyone is gunning for your ring of wishing).

Mixing and Matching

The point of this meandering post is not to say “Thou shall” and “Thou shall not.” Instead, I seek to highlight some of the various approaches to gear based on genre. Rather than adding gear to a game

because that’s how GURPS works, you might consider what sort of gameplay you intend with the gear, and apply it accordingly.

Naturally, these often mix and match. Classic D&D paired gear-as-logistics with gear-as-alternate-progression-track, while later D&D incarnations kept the gear-as-alternate-progression-track and shifted the rest to more gear-as-background. Sometimes, gear-as-background morphs into gear-as-logistics depending on the needs of the group (if your horror campaign leaves the city and goes into the jungle, the GM may care about survival logistics!). Characters might have signature gear as well as gear-as-progression-track if the signature gear is unusually powerful or the player has a reason to remain attached to the item (“This sword may not be the best, but it is my father’s sword); such gear might be narratively important (“It may seem a simple sword, but only it can slay the Lich King.”).

Games often make certain forms of gear very important while pushing the rest to the background. What sort of gear players need to ponder carefully can say a great deal about genre. A typical fantasy game might turn on what armor and weapons you choose, but not care a great deal about the exact nature of your “spell casting supplies,” other than to note that you have them. By contrast, GURPS Monster Hunters or GURPS Cabal (or any game with extensive Magical Modifiers) might care more about what magical symbols and regents you carry on your purpose, but be fine with you having “a generic gun.”

Psi-Wars and Gear

Currently, Psi-Wars uses the standard GURPS model, which tends to treat gear as logistics and alternate-progression-track, while allowing for a smattering of other elements. However, one of the reasons for this post is to begin a series wherein I revisit how I handle gear.

Space Opera as a genre doesn’t care what your character carries around. Luke Skywalker pulls whatever he needs out of his utility belt, and the story never grinds to a halt because Han Solo didn’t bring some medical equipment or toolkit with him. Instead, characters tend to have what they need when they need it, unless there’s some narrative reason for that to be disallowed. If the space princess needs to change out of her battleweave armor and into a fine gown, the GM won’t tap on her sheet and note that she didn’t have one noted on her sheet and then insist that the group spend the next hour working out how to get her a dress. No, she has it, and she can likely even dictate its details and claim a Fashion Sense bonus. It helps that most characters tend to have ships with cargo bays that they can easily justify as having “whatever” in there.

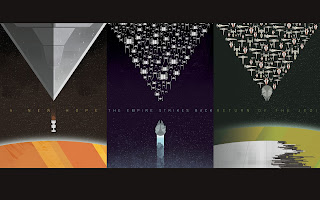

When characters do care about gear, that gear tends to be deeply symbolic. Luke carry’s his father’s lightsaber, and Han carries his signature blaster. People do change out weapons and gear when it suits them (such as stealing stormtrooper armor), but this tends to be momentary and superficial, or the weapons don’t really matter (a rebel blaster and a stormtrooper blaster are both just as good). Characters tend to either have deeply symbolic and narratively resonant signature gear, or they have some background gear.

This is the core reason I don’t see players “trading up” when it comes to gear. While Psi-Wars definitely has “zero-to-hero” elements in it, these tend to parallel those of the wuxia/kung fu genre, where the character needs to learn how to fight or how to master their powers, rather than ditch their old force sword for a better, newer force sword. Characters either have gear because they need it, in which case it tends to be typical gear not unusual for the setting (“I have some sort of blaster”) or a deeply personal and symbolic set of gear. This tends to parallel gear-as-symbol or gear-as-background element.

Characters need fairly regular access to spaceships (that is, anyone who wants one should be able to do it without making it the central thing about their character) and the ability to declare that they possess some sort of signature gear. Beyond that, most everything else should fade into the background: if characters need something, it should either be so commonly available that it wouldn’t make sense for them not to have it (“Do I have a datapad?” “Of course, duh”), their organization should provide it (“Standard issue imperial blaster”) or they should be able to scrounge for it (“Found those power-converters you were looking for”) rather than fussing over precisely how much money they have, though wealthy characters should have a highly noticable advantage over those without wealth: the difference between spoiled space princess and starving moisture farmer should be obvious in gameplay.