|

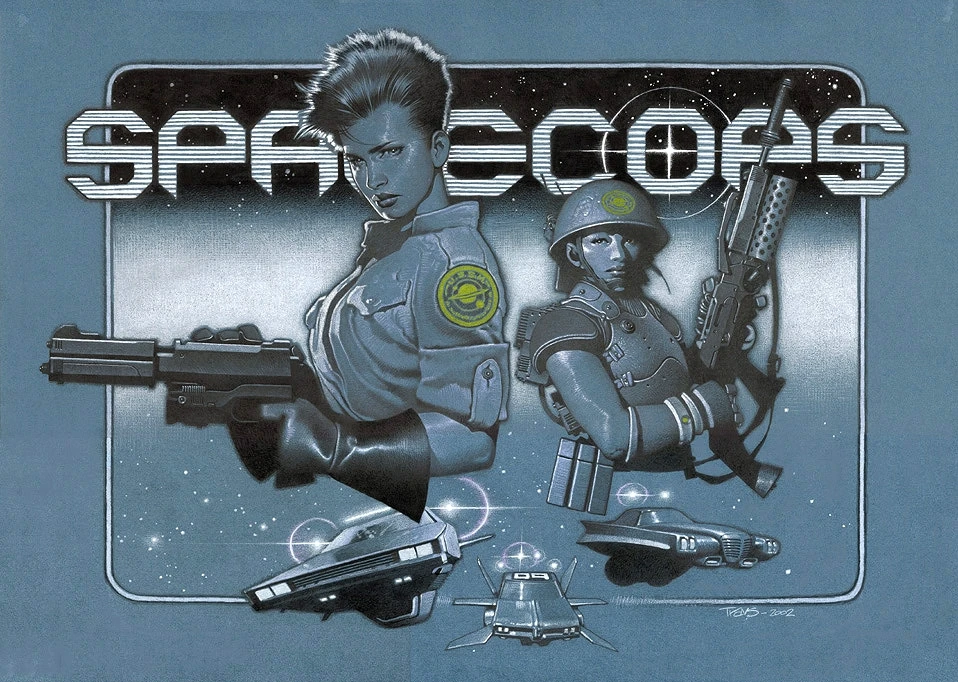

| I’m not saying it was a great movie, but it does a good job capturing how sci-fi aristocracy might look. |

The aristocracy of the Alliance served as the foundation for the Federation that came before the Empire, and the Empire that came before the Federation. It has ruled the galaxy for over a thousand years, and does not intend to stop now. They represent both the golden age of the past, and a chance to bring about a new era for the Galaxy. Today, I kick off a surprisingly long series that takes a deeper look at them, both as organizations and as characters.

Today, I start with noble houses as organizations, what it means to belong to one, and what they can do for you. I want to note that this is a “first draft,” and that the following is incomplete. The deeper I dived into all of this, the more I realized I needed greater detail on spycraft and law enforcement, but I already had the latter for the Alliance in the form of the Constabulary, and the former will require a thorough look at all organizations. Thus, take all that follows as my first stab, just as everything else I’ve written in Iteration 6 has been. I’ll take another look at everything before the iteration wraps up.

I’m also trying something new with how I generate these posts, so you might notice that this is much earlier than the past month’s worth of posts have been. That’s because it was actually scheduled, again.

Noble House

A Noble House isn’t an organization in the classic sense, but rather, consists of a dynasty of powerful and influential nobles who share a collection of titles and a similar lineage. The Noble Houses discussed in the context of the Alliance refer specifically to the noble lineages of the Old Alexian Empire, who created the Federation, and now stand in opposition to the Empire, having formed the Alliance.

When Alexus rose to dominate Maradon and forge his interstellar empire, he had two major assets. First, he had the assistance of wealthy warriors skilled in the art of the force sword, and he had the assistance of the Oracular Order, who foresaw not just the ultimate victory of Alexus, but the desperate need for not only that victory, but the eternal reign of his dynasty. These two elements combined to create the Noble Houses of the Alliance.

The Oracular Order foresaw a million branching “paths” that the galaxy could take, and chose one winding and complex path called “the Golden Path” as the best hope for humanity’s ultimate survival. Alexus could never achieve this victory on his own: his line would need mates that would help breed the line true, allies who would fight at their side, rivals who would sharpen their skills and mentors who would remind them of their purpose. The Oracular Order needed not just the Alexian Dynasty, they needed a host of heroes. For this purpose, they turned to the best of the best among the Maradonian nobility and began to breed them for their ultimate roles. As a result, modern nobility, where its bloodline has remained pure, who have access to specific psionic abilities and have distinct advantages over the common man, with a focus on achieving a specific role within the Oracular Order’s vision of the future.

A Noble House has legal privilege and dominion over certain worlds. As Alexus conquered his Empire, he distributed the rights to rule those worlds in his names to the warriors who helped lead his armies to victory. Their right to rule became cemented by the machinations and blessing of the Oracular Order, who needed their eugenically engineered nobility to shepherd the rest of humanity down the Golden Path.

Taken together, a noble house, then, is political, genetic, psionic and martial tradition dating back millennia. They ruled over the galaxy, and rule over the Alliance today, and fight the Emperor, all in the name of their inherent supremacy and the mandate given to them by the Oracular Order to protect all of mankind. However, the death of the Alexian dynasty and the general dissolution of the Oracular Order ended any hope of fulfilling the experiment they began at the dawn of their empire. Now, the noble houses cling to the tatters of that dream, cast adrift without the guidance of the Oracular Order, with their traditional domains stripped from them by the Emperor, and their genetic purity drifting and dissolving back into the common masses.

Taken in another sense, a noble’s house is literally his estate and those who maintain it. In this sense, a house very much represents a classic organization, but this organization exists to serve the lord. This represents the lord’s armies, the lord’s servants, and his networks of spies and assassins. Described in this way, a noble house consists of servants, commanded by a single lord who governs the entire house. The other lords of a House do not strictly speaking belong to this hierarchy, but that hierarchy does exist to serve them.

The Federation and Old Empire contained dozens of noble houses. The Alliance contains fewer houses (and many houses within the alliance have lost a great deal of their former glory). This document details four houses, meant to be a representative, rather than exhaustive, list.

- House Sabine: A royal house engineered by the Oracular Order to provide a pool of Espers to draw into their ranks and to serve as the consorts to House Alexus. They’re known for their exceptional beauty and fecundity, and the fact that they produce far more female than male children. They have a knack for ESP. The head of their house, the numinous Nova Sabine, Duchess of of Persephone currently serves as the speaker for the Senate.

- House Grimshaw: Technically a cadet branch of the royal house of Daijin, the Grimshaw family rose to dominance during Shio Daijin’s ill-fated attempt to re-unite the Alexian Empire under his rule. The Oracular Order engineered house Daijin (and Grimshaw) to serve as purifiers of the noble houses, ensuring they stayed true to their purpose, and Grimshaw remains a deeply conservative house, often in opposition to Sabine’s more egalitarian politics. They have a talent for ergokinesis. Their head, Bale Grimshaw, Duke of Denjuku is considered the most powerful noble of the Alliance.

- House Elegans: This knightly house lost all of their domains to the Empire, and have returned to the Alliance seeking allies in reclaiming them. The Oracular Order engineered them to be the left hand of Alexus, willing to explore new ideas and to violate social norms to achieve success; they’re a somewhat controversial and complex house, plagued with rumors of regicide and abandonment of the Oracular Order in favor of True Communion, all of which they hotly deny. They have a talent for emotion manipulation and empathy, and make for fearsome duelists (and created the Swift form of force swordsmanship). Their current head is the young Anna Elegans, Marchessa of the Tangled Expanse.

- House Kain: The House of Kain is not a “true” Maradon House. Instead, the original warlord of Caliban, Lothar Kain, blocked a key route from the Maradon arm of the Galaxy to the galactic core. Rather than fight these exceptional warriors, Alexus offered them a place at his side. The Oracular Order tried to turn them into Alexus’ right hand, his faithful hounds that would devotedly follow his orders, but the House of Kain has always forged their own path, and remains a barely tolerated faction within the Federation and Alliance. They have no innate psionic potential and lack the blood purity of other houses, but they have a robust line and a tradition of excellent cybernetics. Their current head is Kento Kain, Archbaron of Caliban.

Agendas of the House

A house exists to serve the interests of its nobles. The nobility must retain and expand their power, so the House guards over their titles and quietly push for new acknowledgment. The nobility must retain the purity of their bloodline, so the House seeks acceptable mates and helps to arrange marriages (and alliances!) between them. The nobility must assert its dominion over the galaxy, so the House invests in powerful corporations and expands their military power.

- A noble has traditionally ruled over a world now dominated by the Empire. He must advocate for its liberation, as well as send agents to the world to support (or foment) like-minded insurgencies, and then once the world has been liberated, ensure that everyone understands his role in its liberation, and restore himself as its proper ruler (even if only as a courtesy).

- A beautiful young courtier has been making the rounds of the Alliance courts recently, and she’s caught a young noble’s eye. The noble needs to be assured that she is genetically compatible with his glorious bloodline and, if so, needs to properly court her, while ensuring that such a marriage remains politically beneficial to him. What is her family like, do they have a noble lineage, and what agenda lurks behind her mask of innocence?

- A rival noble has purchased considerable shares in the corporation that a House has traditionally monopolized. The House must press its legal and traditional dominance of the corporation, while undermining the rival noble’s claims. They must also attempt to uncover the reasons behind the rival’s action, and see if they can find some sort of compromise that leaves the House’s power intact.

- A rival noble looks poised to achieve some victory over an important noble of the house (perhaps winning the hand of a beautiful courtier, gaining control of a valued corporation, or achieving some great honor slated for the House). The house must move to find a way to discredit him. The easiest would be to contrive some insult and challenge the noble to a duel, but that requires martial excellence in the House. Alternatively, the House can find some scandal or some legal violation and bring him up on charges before either the Senate, or the aristocratic courts.

- A noble has tangled himself in some unfortunate scandal! Local planetary authorities demand justice, or a corporation threatens to throw him off the board, or the Senate has begun to murmur about charges. The House has a few options. They can counter accusations with accusations of their own, slinging so much mud that everyone seems dirty, though that threatens to besmirch the house itself. If they can focus on a single target to accuse, they can turn this into a duel. Alternatively, they can focus on protecting the house itself, and leave the noble to stand on his own and sink or swim in the face of the Alliance’s rule of law, but this sends a dangerous signal to the allies of the House, that the House will abandon you as soon as the going gets tough.

A House as Opposition

The stability and power of a House varies. Some Houses are little more than tattered shells of their former glory, while others retain almost all of their political and social clout. The weakest houses, full of little more than puffed up courtiers are BAD -0, but most Houses have at least paramilitary security and defenses, giving them BAD -2 to BAD -5! Given their psionic legacy, most Houses have superior psionic defenses, and should have at least a PSI-BAD of half their BAD, rounded up.

Serving in a House

Servant Ranks

As an organization, a House exists to serve a noble, and in this sense, a noble isn’t in a house so much as a focus of his house. Instead, the actual organization of a house is made up of the servants of that noble. These servants guard the noble’s interests, and help facilitate any actual political rule the noble may have.

5: Steward, Chamberlain, Marshal, Spymaster, Herald, Seneschal

4: Butler, Chief of Staff, Valet, Attendant, Lady-in-Waiting, Guard

3: Head Chef, Footman, Handmaiden, Groundkeeper

0-2: Maid or Servant

The lowest ranks represent a variety of servants serving in different roles. Rank 0 servants tend to work “out of sight” or do “dirty” work, such as scrubbing floors or maintaining infrastructure in the bowels of a space station. Higher level servants work visibly, which means they can catch the eye of the lord and more easily gain higher level positions. Rank 3 represents the most prestigious of the base servant ranks, either running a local department, assisting those who serve the lord directly, or being present at highly visible events attended by numerous nobles. All of these ranks can be replaced with robots, which is especially common among the least prestigious nobles.

Rank 4 represents those who serve the lord directly, attending to his needs, such as dressing him, fetching things at his request, or acting as a bodyguard, if necessary. This is amongst the most coveted positions as a servant, as it allows one close access to a powerful noble. The Butler or the Chief of staff managed all staffing of a noble House, and may choose who to hire and fire, and who to promote to particular positions. The noble overrides his Butler or Chief of Staff when he wishes, especially when it comes to the those who attend him directly; technically valets and such answer to the Butler, but in practice, they fall outside of the typical hierarchy.

Rank 5 servants act as proxies for their lord, or run major elements of his domain. The Steward or Chamberlain represent their lord in domestic affairs, ruling his estate in his stead. They might attend corporate board meetings in his place, handle his finances, or advise their lord on matters of administration (and might have Administrative Rank of 5).

Marshals represent and advise their lord on law-enforcement or military matters and might have Law Enforcement Rank of 5. They usually represent their lord’s legal concerns on other worlds, such as pursuing or arresting criminals in his lord’s name even off-world. They might have subordinates of their own, as deputies or lieutenants (Typically rank 3-4). The enforcers of a house typically have Law Enforcement Powers (Noble Enforcer) [5], which allows them to perform searches (with a warrant!) and arrest people, but only under the jurisdiction of the aristocrat he serves, and the right to kill if necessary, but killings often invite investigation and oversight and may cause a scandal for the ruling noble!

Heralds (or simply “Ambassadors”) represent their lord among other nobles or in foreign courts, and may have Diplomatic Rank of 5. Heralds generally have Diplomatic Immunity [20]; while executing their duties, their lord is responsible for their misdeeds and misbehavior, and the worst a body can do is expel the diplomat at the risk of angering the noble. This means that the heralds of weak nobles must tread more carefully than the heralds of powerful nobles! These characters also often have their own subordinates, called Secretaries and Attaches.

“Spymaster” is an informal position, and those who have it often have a different title (usually Herald or Ambassador). They govern the highly important spy rings that the noble uses to monitor his rivals and, especially, his traditional holdings within the empire. Spymasters don’t usually have a formal subordinate structure, but often recruit Agents who control specific spy assets. These characters might have Intelligence Ranks.

Rank 4+ servants are often Titled nobles with an Ascribed Status of +1.

The master of a House generally has at least Political Rank 6; treat all servant ranks as subordinate to this political rank.

Favors of the House

Servants can certainly pull rank, when in service to their lord, but nobles may also pull rank. Treat them as having a Rank in the house as equivalent to their Status (or, in the case of the ruling noble, the higher of his Status or his Rank of 6). This does mean that a chamberlain has more pull within his house than a poverty stricken knight without rank in any other organizations, but that makes a certain amount of sense: because of his low position, the Chamberlain (or Marshal or whomever) can argue that he serves a greater lord directly; it is not the Chamberlain’s will that is overriding that of a lesser knight, but the pressing concerns of the House Lord.

You’ve probably already worked through Pulling Rank for nobles, but here’s a list of ideas that you might find useful for that:

Entry Clearance (Pulling Rank 13): An aristocrat owns considerable swathes of property, including fleets of ships, industrial complexes and vast palaces. Servants might gain access to any of these as part of their duties, while nobles of the house can expect direct entrance.

License (Pulling Rank 13): Servants often need additional legal permissions to perform their duties, especially Heralds and Marshals. Houses do not grant these permissions, but can expedite them!

Cover-Up (Pulling Rank 14): Nothing may besmirch the honor of his highness! A noble house excels at covering up embarrassments, whether they’re ill-advised trists or completely illegal activity. They definitely perform this for their ruling or associated nobles, but also for servants who are acting in the interest of their lord.

Consultation and Specialists (Pulling Rank page 15 and 19): Noble houses have servants who specialize in fasion (Connoisseur (Fashion) and Fashion Sense), proper etiquette (Savoir-Faire), the history of the house (History) and various mundane household tasks (Administration, Housekeeping, etc).

Bribe/Hush Money, Cash (Pulling Rank page 14 and 16): A noble house has access to extensive tax receipts and corporate profits, and it will happily hand over a “cash allowance” to members of the house if they need a little extra, but this generally applies more to servants, who need some discretionary funds for some of their tasks, especially the less public ones. Note that how much money is available to a house varies from house to house, with Grimshaw and Kain among the wealthiest and Elegans (currently) among the poorest.

Funding (Pulling Rank page 16): Noble houses act as prime centers of funding throughout the Alliance. They tend to fund major war efforts, archaeological digs or major architectural projects out of their own (very deep) pockets. While they rarely fund requests brought to them by servants, they absolutely fund requests made by member nobles.

Gear (Pulling Rank page 16): Noble houses provide whatever materials their servants need to perform their tasks, but they also have access to ancient relics and powerful technology specific to that house. Nobles associated with the house may certainly request access to these features!

Introduction (Pulling Rank 18): The Alliance relies on introductions as its primary form of security. Noble Houses make a point of introducing their members to the members of other houses, sometimes through something as simple as a letter of introduction, or a direct introduction from one noble to another, but preferably through a grand event where the noble is introduced the aristocratic community as a whole. Servants tend not to be formally introduced to other nobles (though heralds will definitely receive letters of introduction, as will marshals in pursuit of justice), but they rub shoulders with nobles regularly. A servant who wants to meet a particular noble might ask very nicely (though likely at a penalty).

Invitation (Pulling Rank 18): Nobles regularly hold grand, and very exclusive, events which serve both to expand the glory of the house, and to Servants rarely get invited to parties or introduced to nobles as such, but they’re often asked to attend events to assist others, and this can bring them into very close proximity to other nobles, where they can be noticed, asked questions, or have a chance to ingratiate themselves to the elites of the Alliance. Noble Houses can also offer “letters of introduction” on the behalf of their servants, or even their nobles, to ensure that the noble is properly accepted by another, more important noble.

Facilities (Pulling Rank 18): The aristocracy controls some of the mot beautiful architectural space in the galaxy, available for the most elegant of soirées. They also control naval shipyards, war rooms and their legendary cathedral-factories, capable of constructing bespoke arms and armor.

Travel (Pulling Rank 19): The aristocracy owns ships. Naturally, they own many military ships, but for that, see Aristocratic Regulars. They also have access to diplomatic transports and personal yachts, all of which can be used to get people from one world to another, and often with a measure of legal immunity to boot! The aristocracy sees itself as interstellar, and can provide that access to the stars to any of their servants or members.

Muscle (Pulling Rank 19): Noble houses have access to military assets, but for that, see Alliance Regulars. This assumes instead that a servant needs some muscle, or a noble doesn’t want to pull on his military forces to push some people around. Most noble houses have some well-muscled men on staff, people who double as bodyguards in a pinch, and a house can generally rustle up some well-dressed knuckle-crackers, if necessary.

Propaganda: Given sufficient time (say, a week ahead of time, but it’s ultimately up to the GM), a noble house can spread a particular idea. Treat this as Compliments of the Boss: A successful request applies +3, a critical success applies +6, a failure applies -1 and a critical failure applies -2. This applies to appropriate influence rolls and to Communion reactions for path-based miracles for the appropriate path. This effect is temporary: usually no more than one adventure (usually lasting no longer than a week: for more permanent effects, buy some manner of Reputation), and only to a single world. The player needs to define the nature of the propaganda up front and it only applies as appropriate (for example, if you spread the idea that you are the reincarnation of a world’s savior, you cannot use it to impress off-worlders or the non-religious, or when you behave “out of character”).

Servant Character Considerations

Requirements: Characters serving in a House as a servant generally have a minimum of Wealth (Average) [0]. This is true of even poor noble houses, as they’ll typically just employ less servants. Diplomatic servants usually have Legal Immunity (Diplomatic) [20], while law-enforcement servants usually have Law Enforcement Powers (Noble Enforcers) [5].

Servants often act as Allies, and typically cost either Ally (Servant; 75 point character; 15 or less) [3], or Ally (Servant; 150 point character; 15 or less) [6]. “Houses” rarely act as patrons, but the ruling noble might. A ruling noble as a patron is 15 points for a powerful house, or 10 points for a weak house, while any ruling noble is worth -20 points as an enemy.