I like to pay attention to corporate boardroom drama, because I find management successes and failures to be profoundly interesting, likely because I’m a computer programmer by trade, and “automating procedures” is what I do, and studying how companies fail or succeed at these things are interesting. So one of my side hobbies has been tracking the management, and mismanagement, or Star Wars since Disney bought it. I’m more interested in the tales of woe from behind the scenes (such as the stories behind why nearly every director for a Star Wars film has been fired before completion, leading to often expensive reshoots and reworks), and it’s not just Star Wars that interests me, but studying up on the stories behind (for example) the Snyder Cut has been very interesting to me as well.

This means I sometimes delve into the rumor-monger parts of Youtube, as that’s where you’ll get these stories, as what comes out in official memoirs is always carefully sanitized. My preferred channel here is Midnight’s Edge, as they tend to be fairly professional and look into the parts I’m most interested in, which is the management stories themselves. There are others, such as Doomcock above, who prefer to focus more on bashing on what they perceive as failures of the franchise, and condemning what they feel are bad narrative choices or “abusing the audience.” To be clear, I think that’s happened, and I think there’s an interesting discussion to be had about the creator/audience interactions on platforms like twitter, and how they go sour, and how the platform itself interferes with those discussions, but that’s not the core topic that interests me.

However, recently, something has happened that I find remarkable. Doomcock, who reports rumors, that he claims to get from inside sources have suggested that Disney might be preparing to “erase the sequel trilogy from canon.” Midnight’s edge hears similar rumblings, but they report it in a more nuanced way. This is not remarkable, as rumor outlets like this are always reporting the demise of their hated foe, Kathleen Kennedy. What is remarkable is how much traction it’s getting, when “mainstream” Star Wars commentators, like trades or Eckhart’s Ladder, start responding to these rumors, and not to “their own sources” but effectively just to Doomcock’s report. That is, we’re getting papers reporting on someone reporting on rumors.

So the first thing I want to say before I go further is to make sure it’s clear what the state of this is: some guy who likes to talk crap about Disney’s Star Wars discussed an unconfirmed rumor he heard from a source who may or may not be lying that Disney is considering erasing the Sequel trilogy, and people are talking about that guy. There is nothing, nothing, confirmed about this. I’ll let you decide for yourself what this says about the state of modern journalism that it’s getting picked up some widely.

Nonetheless, given that it’s hip to talk about, and it touches on several themes important to why I do Psi-Wars, I thought I’d talk about it a bit myself, and what it says about audiences and how you can translate that to your own games.

Seeking Legitimization

Someone once quipped something like “America used to be a nation of people who solved problems; now we’re a nation that petitions management to solve problems for us.” I don’t know how it happened; I suspect the internet and “slacktivism” has something to do with it, but a lot of people seem fixated on “official” things, like Star Wars, and to ignore everything that falls outside of that purview.

The reason Doomcock is reporting on this is because his audience is desperate to hear it, and they’re desperate to hear it because they hate what Kathleen Kennedy has done with Star Wars and they want that frustration legitimized by Disney itself. By issuing a formal statement like “Kathleen Kennedy has been fired because she ruined Star Wars” and/or “We’re removing the sequel trilogy from canon,” it will make this particular fan base feel justified. They’ve largely been maligned by people like Rian Johnson and certain media trades as “Trolls and bots” whose opinions somehow don’t count, and that has incensed them and they need to have that “wrong” rectified.

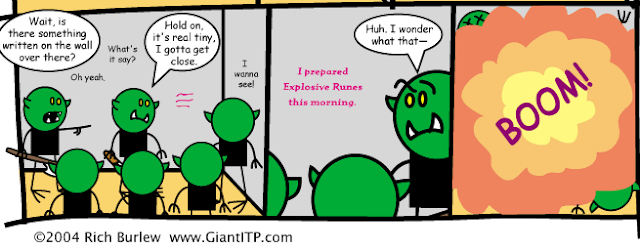

I don’t see it happening, and I don’t see why it’s necessary. This goes back to the core reason behind my call to “Don’t Convert, Create.” A lot of “conversion” happens because people see established properties, like Warhammer 40k, Star Trek, Star Wars and others as “legitimate” and their own work as “illegitimate” and they seek the legitimacy of the establishment. By converting a setting to an RPG, it gives them this illusion of control over that establishmed property: “In my Star Wars setting, I’ll do it right and X will actually be Y.” You see this a lot in fan fiction. There are a lot of problems with this, but to me, the greatest problem is this idea that your own ideas are illegitimate, and that only established properties, specific established properties, actually “count.”

Corporations love this, of course. It’s all the rage right now to pick up a property, lambast any similar properties you don’t own as inferior, and then tell whatever story you want to tell with that particular property, and then criticize those who criticize it as “entitled” or whatever. This creates a perception that their story is the only “real” source from which you can get your enjoyment, so love it or hate it, you must fork over your dollars. This is a good tactic, if you’re a big corporation, but it’s not one that you, as a consumer, should be buying into.

If you don’t like the stories of a property, then stop consuming it. If you liked DS9 and Star Trek: TNG, but you hate Star Trek: Discovery, then stop torturing yourself with Discovery and go back and watch reruns of that show that was great. If you want something new, something fresh, go look around and look more broadly than Star Trek: check out Farscape or Andromeda. The same applies to Star Wars: I prefer the Mandalorian and the Clone Wars to the Last Jedi and I couldn’t make myself sit through Resistance or the Rise of Skywalker… so after a good college try, I stopped and moved on to the things that interested me.

Furthermore, there are hundreds and hundreds of outlets out there trying their hardest to create the product that you want, but are overshadowed by these big, corporate properties. There are dozens of indie RPGs, or niche computer games, or sci-fi authors that feel the same way as you do about X, whatever X is, and are trying to cater to you, but if you’re busy yelling at Kathleen Kennedy, you might miss them and what they’re doing. Imagine how frustrating it would be if you were in their shoes, saying “Oh yeah, I too wish Star Wars had a more mature political environment like Game of Thrones, so I wrote this book, but nobody will read it because they would rather complain about Star Wars.” So, why don’t you go explore those and invest in the authors and properties who reward your investment while discarding those you feel don’t?

And once you do that, once you escape the walled garden of a corporate property, you’ll discover, first, how derivative the corporate property is (not that this is necessarily a bad thing, but let’s not pretend that Star Wars or Star Trek are the most innovative or original properties in the world), and how wonderfully full of ideas the world actually is. You can start to synthesize those ideas into your own world and setting, and you might even find you have an amazing product when you do. Literally every product you love got its start doing something like this. And you can really tell the quality difference between someone who paints by numbers vs someone who dives into the depths of a thousand interesting sources and then collects them into one thing.

Your work is legitimate. Your complaints about an established property are legitimate. You don’t need anyone else to tell you that, or to admit it to you. People who insist on it are putting their hopes and dreams in the hands of someone else, which is a recipe for misery. So don’t do it.

On Creative Evolution

Now, with that out of the way, let’s return to what I suspect is going on inside Lucasfilm and how it relates to you. In truth, the Sequel trilogy certainly choked; whether you believe it did so at TLJ (as I do) or RoS (as the trades are grudgingly beginning to admit), the sales of Star Wars films and their merchandising have disappointed Disney. What hasn’t disappointed Disney was the reception of the Mandalorian! Those toys took off like crazy (everyone wants a piece of Baby Yoda), and you can tell from what’s making headlines in Star Wars news that the Sequel trilogy is out, and the Mandalorian is hip. I hear constantly about stars trying to get a role in Mandalorian Season 2, but crickets about the next set of Star Wars movies.

So, imagine for a moment that you’re writing the Mandalorian Season 2, or a new animated series, or the Obi-Wan series: what is your focus? Is it on the sequel trilogy? Probably not. Here’s what I suspect your likely sources are: the original trilogy, the prequels (especially if your work is set in an older period), the works from the Expanded Universe (to be strip-mined for ideas), and broader works of fiction (again, to be strip-mined for ideas). And you’re going to write what you need for your show. If you’re discussing the Mandalorian, you might want to focus on stuff that also dealt with Mandalorians, like the EU’s discussion of “the Great Hunt,” or maybe you’d borrow from Predator because an episode where the hunter is hunted might be interesting, or you might take him on an adventure off to a distant land, based on some pirate story like Treasure Island; you might reference Ord Mandel, as they talked about it in the Empire Strikes Back in reference to a Bounty Hunter, so maybe it’s a place a bounty hunter should visit, etc. That’s where your focus will be: pulling material that will help you create the best work you can from the hear and now.

The Sequel Trilogy helps you very little. First, it’s set in the future, so at best it’s something you work your way towards. You can’t introduce Snoke or Kylo Ren in the Mandalorian, because those characters are in the far future from where the Mandalorian is. Even if you were going to, what will you introduce? The sequel trilogy had a problem (one that was not of Kathleen Kennedy’s making) in that it chose explicitly to retreat the original trilogy. It gave us a new Empire and a new Rebellion, new Jedi and new Sith, which created this perception of this being a “second rate original trilogy,” a copy rather than an original. They did this because they saw the prequels as “risky,” and retreading the original trilogy as “safe,” and it worked: it filled seats in a theater. But for the long term you’re left with a problem. Now, if you want to tell a new story about imperials fighting rebels with only a few force users valiantly defending the rebellion while a dread and dangerous force user stalks our heroes, where are you going to tell it? In the original trilogy era, of course. It’s all already there. What benefit is there to telling it in the sequel era? What do you gain? Nothing. The prequels (and other settings like KOTOR) have the benefit of supporting other sorts of stories. And that’s really what you want out of a future setting: it should allow you to tell new sorts of stories that you couldn’t tell in the modern era.

Worse, the sequel trilogy have the emergent quality of invalidating the original trilogy. To create an empire and a rebellion, you must undo the heroic and righteous New Republic that Luke, Leia and Han sacrificed so much to build. So if you want to write something between the OT and the ST, you have to write about how the heroes of the OT totally screwed everything up, and I don’t think that’s a story Star Wars fans want to read, or Star Wars writers want to write.

So here’s what happens: you write the story you want to write, now, and in the present. You don’t consider the sequel trilogy because you’re not writing in that era (and you don’t really want to anyway) and because it doesn’t offer you anything interesting that you don’t already have. And you’ll let your story go where it necessarily needs go to. And in so doing, you’ll start to devise setting changes that support the story that you’re trying to tell, and that will inform the development of the setting. If the evolution of the setting towards the First Order and the Resistance supports future Mandalorian episodes, then those elements will get included, but I don’t see that happening. There’s very little interesting in the sequel trilogy that would make for a better Mandalorian episode or for an interesting 5 seasons of an animated show.

Not Erased, but perhaps Forgotten

What naturally emerges from this process is that material that isn’t useful slowly gets winnowed out. If the sequel trilogy serves no purpose to the story you write, you won’t use it, and if nobody uses it, it’ll slowly get replaced by things people do use. You don’t need to make a sweeping statement about how you’re not going to use it, and it’s not even useful to do so: it would alienate the talented people that worked on it, and it might be that you do want to use some of it.

What will happen, inevitably, as this process continues is that the Sequel Trilogy, where it isn’t useful, will fade into memory, in the same way that the Christmas Special and the Ewok films did. Nobody came along and declared them “Non canon!” but people just ignore them. They’re relevant primarily as trivia.

And yet… In the first episode of the Mandalorian, a bounty mark mentions “Life Day” which is a reference to the Christmas Special. As I mentioned above, if it’s useful, people will use it. “Life Day” is a holiday, and if you need the mention of a holiday in Star Wars, why not that one? It’s a nice nod. Even for things that nobody likes, that people wish would just go away, there are still neat ideas you can mine.

Audiences, including your players, tend to form a “head canon,” the things that stand out to them and make sense. They begin to treat something as “standard” and other things as irrelevant. For example, there is never once a mention of “the light side” in the original trilogy. In fact, the Jedi and the force is much more subtle in the original trilogy than in the prequels or the sequels. The original depiction of the force had “the Force” which was in balance, and “the Dark Side” which represented a disbalance in the force. Luke “bringing balance to the force” was about exising the Dark Side. But we don’t treat it like that anymore. Now, we talk about a “light side and a dark side,” like a yin and a yang, and balance was eliminating both too much light and too much dark. The idea of the “Grey Jedi” as a truly balanced person was introduced slowly, as a logical conclusion of this thought process. The creators didn’t will it, they didn’t force it on the audience, the audience came to that conclusion and the creators accepted it.

This happens subtly and I predict it will happen with the sequel trilogy. There are elements that I think even the detractors of the sequel trilogy like, or just assume are part of Star Wars now. These include (among others):

- There’s an imperial remnant called the First Order somewhere out there

- There are other dark side users out there plotting

- Leia and Han have a force sensitive child named Ben Solo

- Stormtroopers aren’t clones, and they can decide to go rogue; they can have personalities.

- Jakku

- The advanced look of the First Order and the new X-wings

Most of these were put forward by the Force Awakens which, to my eye, excited Star Wars fans the most. J. J. Abrams is very good at creating an interesting and engaging mystery box, and most of the objections to the sequel trilogy arise from objections to how those mystery box elements were treated (and the way the ST invalidates much of the OT). I predict, just like how Life Day from the Christmas Special, you’ll see these elements slipping into Star Wars canon because they’re useful and because everyone assumes they were always true. They might not be alone: the First Order might be one of many imperial remnants, we will certainly see a variety of new worlds, we might see new Dark Siders emerge, who may or many not compete with Snoke (who may or may not appear in the continuing Star Wars sagas).

This finally brings us back to you and your players: if I were you, I’d watch for these sorts of Head Canons popping up. Players assume things work a certain way and will begin to operate that way. This may or may not be true based on the material you’ve created, but you need to be careful about correcting “head canon.” It can create hostility. In a very real sense, the audience and creator cooperate to create the shared story between the two of them. It’s an illusion that the audience is passive: how they receive it can and should shape how the creator continues to create. And this is never more true than for an RPG.

So anyway, in conclusion, I think this whole rumor is a tempest in a teapot and safely ignored. The “erasure” of the sequel trilogy, if it occurs, will be piecemeal and slow, a natural evolution of the needs of current Star Wars creators. It will not completely erase the ST, as there are some useful elements in there, but I predict not enough to keep it whole in the long term. I don’t think you’ll ever get a grand, sweeping statement of the non-canonicity of the sequel trilogy, but even if you hate the sequel trilogy, you really don’t need it. Just consume the things you like, and ignore the things you don’t.