If you enjoyed my Martial Arts as power-ups series, and you’re just now joining us, you can see four more worked examples for Psi-Wars, my Space Opera setting:

Please note that Psi-Wars uses a “Technique Proliferation” optional rule: the costs of techniques are halved.

I wanted to take a moment and address some feedback and thoughts. This turned into quite a retrospective, so I hope you don’t mind long posts.

Feedback!

My discord was absolutely hopping over the past couple of weeks. Some of it involved corrections and critiques, but most of it involves speculation and and discussion of the styles themselves. This discussion rather proved my point for why I wanted this sort of structure in the first place. While I’ve added a few new abilities and concepts to these, most of the moves and abilities have been there for literally years now, but for many people, it’s like they see them again for the first time. Having things laid out so plainly, as in “This is what your character will look like at this level,” really changes the dynamic of how one interacts with the martial art, I think, and it brings it alive. Yes, it’s quite some work, but a lot of the work I put into these helped me think about the martial art and how players would use them, which makes them more usable and the moves themselves help illustrate to the players how to use them.

Some common themes included:

Can I combine these styles??

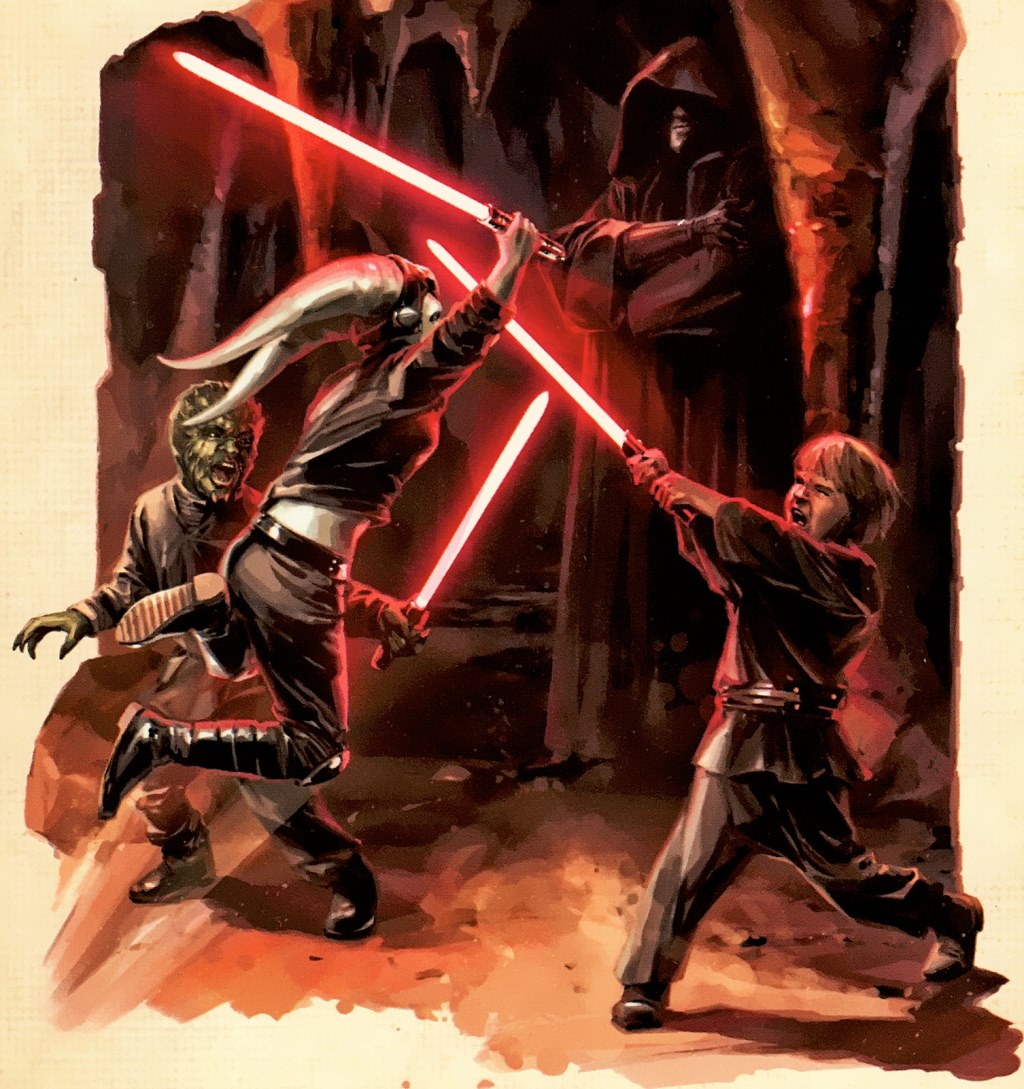

Of course. The idea I had behind them was that one could advance in them in 25-point chunks, as that’s become the Psi-Wars standard for a “power-up.” I also try to leave at lest 25 points in a template’s discretionary budget, so as a Space Knight if you just want to “advance to the next level,” you can do so. But one of the reasons I’ve done a lot of the things I’ve done is because I quite like Wuxia and other martial arts games, which likes to go into the differences in philosophy and approach between different styles, but also likes to explore the merging of multiple styles. This is why Psi-Wars has groups like

the Threefold Order: to encourage people to learn multiple styles.

Anyway, one thing I quickly discovered when I was noodling with these concepts is that if you follow the student/adept/master route again and again, you end up with a ridiculous amount of redundancy. A lot of training goes into getting you up to snuff with the force sword (I’ve tried to follow a schedule of Student=16, Adept=18, Master=20) and precognitive defense and a few other basics (like learning Armoury so you can make your own force sword), as well as teaching you the fundamentals of that particular style (Acrobatics for the Graceful Form, Brawl for the Destructive Form, etc). Once you’ve already learned all these things, once you’ve mastered one style, there really isn’t much point in learning that stuff all over again. A Master of Destructive and Swift is definitely going to be a better force swordsman than someone who’s just a master of two, but his armory isn’t going to be twice as good, nor his Precognitive Defense (at some point, that’s “enough” unless you’re using a style that really focuses on it). So I came up with the “Secondary Style” concept, which is half price. So not only can you combine them, you can do it on the cheap!

I don’t want to use (all) of your stupid power-ups.

At least one person took a look at everything and immediately began complaining that while he liked X, he didn’t like that it was tied to Y. This is, IMO, inevitable. It’s sort of like asking someone what they want for dinner and they shrug, and then when you ask them for specifics (“Do you want pizza? Do you want hamburgers?”) they begin to fixate on specific details they don’t like, which may be annoying, but it’s part of the process of narrowing down on what they do want.

A power-up system like this is very illustrative. It can really show you want a martial art can do, but it also puts you on rails and says that you have to do it. Some people, having been informed by the first aspect of these power-ups, rebel at being forced down those specifics. Now that they can see what they can do, they want to do something else.

I think this is okay. I think this is part of the reason you make these power-ups in the first place. For me, they’re sort of like the Templates of DF or other games: they serve as a powerful inspiration and some people are going to be fine using them directly. But if they’re not, that’s what the second chapter on “Traits” in all of those books are for: to help you customize and build to your specific desire. This is one reason I have the “Martial Art as Style” section in each one, though be warned that those far pre-date the power-ups, and while I’ve tried to update them with the new elements and abilities, they’re not perfect matches.

How you and your GM feel about this depends on how you feel about Templates vs Free Choice. There are people on both sides of the argument, and you can see those argument play out in more detail in the discussion on how to handle power-ups below. “Gating” can create interesting structures within a game, forcing players to make choices that they wouldn’t make without that gating. I personally find that sort of thing compelling, but a lot of people joined the GURPS community precisely to get away from gating and to fully customize their characters. If you find that you really don’t like any of the styles but want to make some sort of highly bespoke mishmash of styles, that suggests to me that there may well be a new niche you can explore in the form of an entirely new style and, hopefully, these styles provide some blueprints for you.

How should I use these Power-Ups In Play?

So, you’ve built a space knight. Perhaps he’s a Student of the Swift Form. You look forward to a new Move, or reaching the level of Adept. You play your first session and the GM hands you 3 shiny new character points. What happens now?

Well, as with everything, this depends on the group, the GM and the philosophies behind them. Let me offer three different ways to use the power-ups

Power-Ups as Strict Path

What happens is you bank those points until you have 25, then you advance.

This model assumes that players must buy the power-ups in blocks. You either have them or you don’t. This means that a character spends might spend a whole adventure as a student and then, suddenly in the next session, become an Adept. This might strike some people as jarring, but I find it no more jarring than a character “suddenly” leveling up in D&D. I find that people who like this sort of thing tend to structure their campaigns in the same way a TV show might structure its seasons: the characters remain relatively static throughout an entire arc, and then the characters get “downtime” between arcs where there characters “level up,” so your student might be a student throughout the whole course of a rebellion, and then in the next arc, focused on aristocratic politicking, he’s clearly advanced to Adept and has some new tricks.

The downside to this sort of approach is that it really delays gratification and it can seem jarring, as noted above. The upside is that it’s probably the simplest to handle.

Power-Ups as Loose Inspiration

You spend your points on whatever you like. Here’s some ideas!

This model works basically like GURPS already works: you get points and you spend points, assuming your GM allows what you’re trying to buy. Your limits in this case are the “Martial Art as Style” not the “Martial Art as Power-Ups.” That is, you can only buy what it lists in your style, but you can do so in any order. So, you might buy force sword and then more force sword and then even more force sword and never improve your Precognitive Defense or get Armoury, and you might grab Power-Blow even though you have no “Moves” for it in your style, but it lists it in the style itself. This is how GURPS already works, and in this case, the power-ups act as a sort of suggestion. You should consider increasing your Precognitive Defense; you should consider the following Trademark moves; when you achieve skill 20 in Force Sword, maybe you should consider getting Armoury and building your own force sword, etc.

The downside to this approach is that you get no consistency between characters. The concepts of “adept” and “master” don’t really mean anything except overall capability and what people are willing to recognize (rather realistic, that). It also really softens the concept of a style into a general philosophy of war rather than a set of cool moves. It has the upside of maximizing player flexibility, and if they have points, they can spend points.

Power-Ups as a Path

Pick your next move and/or exercise and/or level of advancement. You can spend points on any traits within those.

If you want to retain the structure of the power-ups but you want people to spend immediately, let the players set “goals” for their next traits and then spend their points on them. In this case, the Power-Ups have a lot more weight, especially in the form of prerequisites: if you want the First Strike perk, you need to have completed the Adept level of the Swift Form, and that requires you to have the listed traits. That means anyone with the First Strike Perk is, effectively, an Adept as listed.

I find approaching styles in this way helps illustrate how someone might teach a character. If you’re a student learning the adept level of the Swift Form, then suddenly you’re concerned with your Basic Speed (your reaction time) and with gaining more knowledge with your force sword and precognitive defense. You can almost see a teacher pushing a character to move faster and faster, to react now now now, and in so doing, improve these specific traits piecemeal. Perhaps you first learn +1 force sword, then you get +0.25 Basic Speed, and once you’ve achieved all the traits, your master looks at you with pride and pronounces you as an Adept… and then says you’re ready to begin your real training.

If I were to pick an approach, I would personally use this one. I find it the best of both worlds. I’ve tried to make the Master level of each form sufficiently compelling with some unique perk or ability that players will feel rewarded for fully following the path to the mastery of their form. All that said, I think once you start breaking up the upgrades like this, some players will question why they must get some particular trait that really doesn’t suit their character, and if you give in, you find yourself back to the “Power-ups as Loose Inspiration,” but there’s a continuum of strictness there, and I don’t personally think it’s too bad if people have some variety within their forms. Realistically we expect some regional variations and different practitioners will have mastered different aspects of the style; moves helps cover this, but it might not be enough for some players, and that’s okay.

Are Trademark Moves Worth It?

A particularly twinky fellow pointed out that you didn’t actually need to get Trademark Moves to be effective with this new system. Now, a quick aside: a lot of designers hiss and spit at “twinks and munchkins,” but I’ve been in IT long enough to know a rigorous tester when I see one, so I always welcome the thorough fisking they give my systems, because they can show me breakpoints. You don’t have to listen to them if you have good reasons for allowing them to stay, and trying to make a system “break proof” at the cost of other things (like your sense of fun) is usually a bad trade, but they still offer some good insights.

The first point is that you don’t “need” Trademark moves. Well, you never “needed” them, they were introduced as a way of speeding gameplay. If you know Counter Attacks and hit locations and Committed Attacks down cold, then you can improvise a Committed Counter Attack to the Vitals without breaking a beat. If you don’t, though, you either sift through a couple of books to find the modifiers and rules involved, assuming you know these are options anyway. By thinking about them and writing them down, or having someone else think about them and write them down, gives you ideas you might not have had in the first place, and means you can speed up play by saying, for example, “I attack with Dog’s Defeat!” rather that “I All-Out Attack (Double) for a Feint and then thrust for the vitals (-3).”

But are they worth the price you pay for them? Originally, Trademark Moves rather generously gave you +1 to everything in a move, even if it came from multiple skills. So, for example, if you have a move that’s a rapid Grapple/Knife attack, you get +1 to both, while a technique or a skill would only give +1 to one aspect of it, and often be more expensive anyway (+1 to a targeted attack is 2 points for the first level, and for a whole skill is obviously 4). Now, with halved technique costs, that cost savings becomes more dubious. Your +1 feint is 1 point for the first level and a half point after that, and your TA is the same. Getting a +1 to both for one point is… about like buying them as a technique, and the technique is more broadly useful. Of course, it applies to more than just a single skill or a single set of techniques, but a single skill and a single technique applies to more than just a single move, so it strikes me as a wash. But the point of a Trademark move was to reward you for writing all those details down. It was meant to encourage you to speed up play. Is it enough encouragement when maybe you’re better off with techniques and skills?

We could lower the cost of trademark moves. If a trademark move gave you +2, or one point bought you two trademark moves, then it becomes more worth it, and it also better addresses the fact that there’s a soft cap on how many useful trademark moves you can really buy, which might be an issue in a kung fu game. But this also moves us deeper into “half-point land” which SJGames has been wisely trying to avoid. I tip toe there to make skill nuance more palatable, but we can take it too far.

Another possibility is to make Trademark Moves free. After all, the point is to reward someone for writing their moves down. Some GMs give people a +1 for a cool description, why not a free +1 for speeding up play with your pre-written trademark move? The downside to this is that once players realize they can get a +1 for all of their moves for free as long as they do the bookwork in advanced, it risks feeling required. Some players who will write up 20 trademark moves, and lavish in the free +1, and those who already find GURPS a little too bookish will be turned off by the required “homework” of writing out all their moves in detail. A better option might be to give everyone a “free” number of trademark moves, say three, or one free trademark move and then whatever they get from the “moves” that they buy. (sort of like how GURPS suggest you allow 1 perk per X number of points spent in a martial art, you could create a similar equation for X free Trademark moves).

Someone also raised a point about Targeted Attacks and the bonus defense if someone uses them repeatedly. I pointed out that this would probably be true of Trademark Moves as well. I’d caution against using either rule, because their intent was to prevent people from buying one trick and then doing it over and over again (“I take TA (Rapier/Vitals) at -1, and then a Trademark move for attack to the vitals so it’s Rapier+0, and then I attack the vitals, I attack the vitals, I attack the vitals…”) and making the game boring. The problem with this is that players invest points in these, points that are dubiously spent at best (those 4 points could have just been spent in Rapier for a +1 to everything, possibly including parry…), so I’m loathe to punish them. But, if you make Trademark Moves free, then it becomes easier to justify punishing a player who keeps doing the same move over and over again.

I think for now I’ll stick with the 1-point Trademark Move, but I’ll keep an eye on it.

Spinning Attack and Feint

One correction someone issued to me was that you can’t combine spinning attack and deceptive attack. I double checked the book and discovered they were right. My first reaction was to scoff and decide that this was yet another example of how Martial Arts is a little too conservative with what it will allow you to do and not do, but then I started to think about it: why wouldn’t you allow these things to be combined?

To me, Spinning Attack is just a sort of combined Feint and Attack, and you can combine a Feint with a Deceptive Attack, no problem. I think the idea here is that the Spinning Attack is, itself, a specific implementation of a Deceptive attack: that is, by spinning, you’re deceiving your opponent, but to me, a feint is also a form of a deceptive attack (a classic deceptive attack is a “fake out and then attack, which is best handled as a Rapid Feint then Attack).

The problem might be that Spinning Attack is potentially too powerful for allowing that sort of thing. If I have skill 18 and you have skill 12, and I perform a spinning attack, the result is that you lose an average of -6 points from your defense and I lose nothing from my attack; if I also drop my attack to 12 to hit you, you’re at -9 to defense. With a rapid strike feint/attack combo, I’m at -6, so my feint is 12 and I can’t actually make a deceptive attack, unless I’m trained by a Master or I spend fatigue, in which case then it’s Feint 15 (average -3 to your defense) and I can make a deceptive attack of -1 or -2. The downside to Spinning Attack is that it’s possible that I’ll screw my roll and you’ll actually get a bonus against my attack (which, presumably, you could turn into a Riposte). The net effect of this is to make Spinning Attack a preferred technique of people who vastly outclass their opponents, so they don’t risk suffering the penalty involved, and allowing deceptive attack on top of that would really double things up too much. And, of course, the other counter argument to Spinning Attack is that the guy who Feints can do the same thing if he’s willing to just wait a turn.

This creates a weird sort of situation. First, the point of deceptive attack is to eat up your excessive skill. The reason you get skill-25 is so you can make absurd deceptive attacks. If you have such a high skill, you’re basically wasting it on your Spinning Attack, so you burn it on hit locations, like you’ll do a Spinning Thrust for the Vitals, or a Spinning Kick for the Skull. It also feels like it’s trying to fix the wrong problem: if the problem is that someone can accrue too much skill penalty by using Spinning Attack, so they need to cap how much penalty you can apply, so you’re not hitting someone with a -9 to their defense so casually. But then, shouldn’t you fix that by capping the skill penalty?

It seems that Spinning Attack is designed to be the most interesting when characters actually don’t have super-human levels of skill, and their skills aren’t actually that far apart. If I have Karate-16 and you have Karate-14, I could make a -2 deceptive attack and reasonably hit you, or I could make a Spinning Attack and get a -2 and use that little bit of extra skill to hit a hard-to-hit hit location (such as your face). At this point, I risk not only failing to get the bonus, but giving you a bonus. That’s interesting, in a way that the Karate-20 vs Karate-12 isn’t. You’ll actually want to know what your roll is, because it might determine who wins the fight, rather than whether you kill him this turn or next. In this case, what we’re looking at is likely a maximum of +2 or -2 to defense, and this makes sense: if you really screw up your spin, you might expect to Telegraph your attack, in which case your opponent gains a +2 to defense.

So, let’s consider a different possibility: a spinning attack is a quick contest, if the attacker wins the contest, his opponent is at a -2 to defense; if the defender wins, he’s at a +2 defense; if they tie, no change. You can even add a rule of 16 in here to keep it at least a little interesting (so if you roll a 17 while you’re at skill 20, your opponent might still see through your spinning attack). Then you can add a deceptive attack on top of it, no problem, and you don’t have to worry about extreme cases like “Spinning Attack-25 vs skill 12”

If you’re worried about that, though, isn’t Feint a problem? I often see people complain about Feint, especially as a technique, because for 5 points (in standard GURPS; 3 in Psi-Wars), if you’re willing to spend an action, you can give your opponent -4 to their defense, assuming all things are even, and if they’re not, hoo-boy. Plus you can stack up a deceptive attack. It’s a pretty common one-two punch: take my maxed out DX character, hit your opponent with feints until you land that -10 to defense, then make a deceptive attack to demolish them, rinse and repeat. The only thing that really prevents it is that players get impatient, but I see it a lot in duels. This is also why Evaluate exists: evaulate for three turns, then feint to get an average of -7 to defense against an evenly matched foe, then attack with as much deceptive attack as you can, and you win, especially in a game like Psi-Wars where you’re slinging around 8d damage during a duel.

One thing I did with Beats is to cap the penalty at -4. My reasoning was at some point, if you’ve beat your opponent so badly, aren’t we really talking about some level of disarm instead? I mean, it’s one thing to knock an opponent’s weapon out of line, but it’s another to Beat your opponent when you have ST 25 and he has ST 10. I mean, what does a -10 to defense even mean in a case like this? It means he doesn’t have a weapon anymore, is what it means. It’s also weird that your weapon can be so far out of line, but you can attack just like normal, which is why my optional rules also penalize attacks with the weapon. Once you hit 5+, your weapon becomes functionally unready (though I’ve changed it to “you can’t attack or parry with it until you ready it or the end of your next turn” to allow people to just wait it out, especially characters with a second weapon or second mode of attack, because requiring a ready is a hard missed turn).

So why not apply the same logic to feints? If we cap a feint at -4 and offer some special benefit for extreme rolls (though I don’t know what that would be), it represents the maximum sort of benefit you can get from faking someone out. That does cause problems in extreme games (Force Sword-30 vs Force Sword-30), but if the characters are close in skill, they won’t see much benefit from Feint anyway (usually no more than -4 if they maxed out the technique) and the characters will be slinging around pretty extreme deceptive attacks that eat up their extreme skills anyway (if both characters have Defense 19, but they’re using -18 deceptive attacks to apply -9 to active defenses, then a feint with -1 to -4 is plenty at even high levels of play).

Just something to consider. I’ll let my discord chew on it before instituting it in Psi-Wars, but I think it might be a good idea.

Basic Move and Encumbrance

A reader finally explained their rabid distaste of any encumbrance at all to me, and I was shocked to realize I had been running it wrong ever since I got 4e. See, back in 3e, you had a straight penalty from encumbrance: Light Encumbrance gave a -1 to Dodge and Move, Medium gave a -2, and so on. With 4e, this was changed to -1 to Dodge and ×0.8 move and Medium was -2 and Move was ×0.6 and so on. This worked out to be the same. If you were Basic Speed 5, at no Encumbrance you had a Dodge of 8 and a Move of 5; at Light you had a Dodge of 7 and a Move of 4; at Medium, you had a Dodge of 6 and a Move of 3, and so on. This is still true in 4e.

The problem is that you round down when it comes to fractions. So, in 3e, once you hit move 6, one level of encumbrance in 3e dropped you to Basic Move 5 (+1 when compared to someone with Basic Move 5 and Light encumbrance), but in 4e, it drops you to Basic Move 4 (as though you never bought +1 Basic Move at all). I personally find this repugnant. I thought the rule was in place to handle extreme cases (like a character with Basic Move 10 and -5 from Extra Heavy Encumbrance dropping to a Move of 5 while also having a Step of 2), while operating more or less the same at more realistic levels (Basic Move 4 to 6); what it does instead is encourage pretty heavy investment in Basic Move: Basic Move 10 is actually a lot better than Basic Move 9, because it gets +1 step, and +1 Move at almost every level of encumbrance.

This seems so strange to me, so I did the math to see what the differences were. I would expect that whatever system we use should more-or-less work at human normal values (Move 4-6) and then become more proportional the more extreme you become

|

|

Light Encumbrance |

| Move |

Step |

3e |

Round down |

Round up |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 3 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| 4 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

| 5 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 6 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

| 7 |

1 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

| 8 |

1 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

| 9 |

1 |

8 |

7 |

8 |

| 10 |

2 |

9 |

8 |

8 |

If we look, 4e’s “Round down” matches perfect at low values, but fails at a weird breakpoint at Move 6, which is the most likely to be encountered by a player. Round up, by contrast, fails at Move 4, which is effectively “free points” if you know you’re going to be encumbered anyway. So, you have to pick your poison: do you want to make players waste 5 points in Move 6, or get free points at Move? SJGames favors “no free points” so I can respect what they’re trying to do here. Furthermore, if you want to change it, where do you set the breakpoint? You can say “Well, Move 6 work differently,” okay, but then Move 7 breaks. So, we say “Move 6 and 7 work differently” but then 8 breaks, and so on. Where do you draw the line?

Move 10. I draw the line at move 10. Say Move 9 just gets a -1 to 8. That means when you improve to Move 10, which is also 8, you gain no bonus… except you now have Step 2. So that seems fair. Great! Problem solved. I’m a genius.

Except…

|

|

Medium |

| Move |

Step |

3e |

Round down |

Round up |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 4 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| 5 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| 6 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

| 7 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

| 8 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

| 9 |

1 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

| 10 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heavy |

| Move |

Step |

3e |

Round down |

Round up |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 5 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| 6 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

| 7 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

| 8 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

| 9 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

| 10 |

2 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

|

|

X-Heavy |

| Move |

Step |

3e |

Round down |

Round up |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 6 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

| 7 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

| 8 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

| 9 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

| 10 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

If we look at Medium encumbrance, we start to really diverge from the 3e and 4e point at Move 8, and for Heavy, our “you get nothing!” happens at move 7 already! We also start to get “free points” pretty quickly. By X-Heavy, it doesn’t matter what your move is, you’re floored at Move 1 until you hit Move 10 (unless we round up, in which case Move 6 is enough; it’s interesting that if you use the Round Down system, X-Heavy encumbrance means you can ONLY move ONE STEP until you hit Move 15). You can also see that X-Heavy gets into some BS pretty quick in 3e. Even if you accept that Move 2 is fine for someone with Move 6 and X-Heavy encumbrance, is Move 7 really 3 times as fast as Move five at X-heavy encumbrance? Hmmm.

So, I had a knee-jerk reaction against the idea of someone with Move 6 losing all extra movement that they purchased once they put on some leather armor, but when you explore the full implications, you begin to see why it is the way it is. I still think you could probably find some middle ground between the easy 3e system and the much stricter 4e system, and Round Up offers some interesting possibilities but it also has some drawbacks that aren’t worth it. The truth is, you’ll get breakpoints somewhere, and 4e is built to give you more bang for your buck as your points invested get higher. So, yeah, if you want to move quicker in Light Encumbrance, get more ST (this makes ST more valuable anyway) or go up to Move 7. I bow to their wisdom.