So, previously, I had a post on making a map in general, but the problem with Psi-Wars, and space-based sci-fi in general, is that astrophysical realities make map-making in space especially challenging. I wanted to spend a post talking about these difficulties and how I plan to fudge things to make it work for Psi-Wars.

I also want to comment that I’m not entirely happy with this post. Galaxies are pretty complicated, and this post was already running long, but I hope I captured the sort of core issues that one faces when going from the surface of a planet to the black sea of the stars.

The Astrophysical Problems with a Galactic Map

Quick, I want you to think of Star Wars, and I want you to picture a map from it. Can you answer some of the following questions:

- Where is Tatooine in relation to Alderaan, Dagobah, Hoth and Yavin IV?

- Which is closer to Coruscant: Tatooine or Naboo?

- What are the worlds around Alderaan like? What similarities do they share?

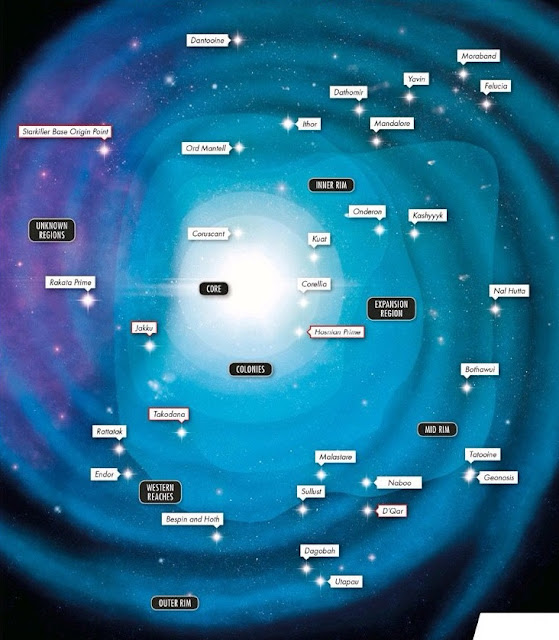

Can you answer any of them? I have a map above, but note that I’ve seen other maps that conflict with it, such as the galactic maps found in Empire at War, so you can use that map if you like, but try to remember. And contrast this with, say, your knowledge of the map of Middle Earth (in which direction, from the Shire, does Mordor or Lothlorien lay?). Personally, I find it very hard, to the point of irrelevance. I’ll offer one example: Naboo is closer to Coruscant than Tatooine, so why would the Jedi, in The Phantom Menace, choose to go to Tatooine to get parts rather than some other world on the way back to Coruscant? The answer, I think, is because “astrography” isn’t a major concern of the Star Wars writers, and it won’t much impact your Star Wars campaign either. If your characters want to go somewhere, they do, and you can place star systems in vague areas (“Tattooine is far from the galactic center, and in Hutt Space.”) and that’s fine.

This doesn’t mean crafting a star chart is pointless, just that if you’re going to do it, you need to give some real thought to why you’re making the map and what it offers you. A map, if I may sum up my previous post, exists to explain geographical realities, such as distances and relationships between the themes and elements of your campaign. The problem with a galactic map is that it’s not geographical; a geographical map is literally set in stone, as it measures the earth, while astrophysical maps measure the stars, and the stars work very differently. You can use this difference to your benefit, especially in that if addressed face on, it forces you to answer questions that might prove interesting and offers options that really set your game apart from typical fantasy fare, but dogive some additional consideration to any stellar map you’re going to map.

Most of my discussion focuses on galactic–scale maps, as that’s what Psi-Wars uses, but I’ll try to briefly touch on some general topics as well.

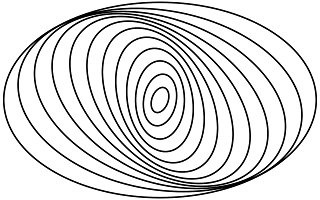

1. Three Dimensional Thinking

This actually doesn’t matter too much for galactic maps: a galaxy is hundreds of thousands of light years across while less than a thousand light years thick (at least with the “thin disk” part of the galaxy). By comparison, if a dinner plate is about 10 inches (25 centimeters) across, if it had the same dimensions as a galaxy, it would be about a millimeter thick. That’s not “paper thin” but it’s close enough that most people would think of it in two dimensional terms. I’d like to note that this is a case where most sci-fi actually skews the wrong way: they tend to overemphasize the three-dimensionality of galaxies because they know that space is three dimensional.

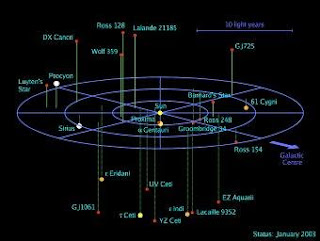

This sort of topic comes up more in smaller-scale sci-fi settings. Given that stars are actually scattered across a three dimensional space, it makes sense to depict them like that. Personally, I rarely see players fuss over that, because working with a flat piece of paper is easier than working with a three dimensional model. I find the extra dimension doesn’t really add anything: it’s not like “Up” is harder than “Down” or anything, and you can effectively reorient that three dimensional space in whatever way is convenient for you, so little is gained by emphasizing it. Nonetheless, it can earn you brownie points with purists. There are a few ways to tackle this, but the easiest is make a notation by each star how many (interstellar units you care about) the star is off the plane depicted by your map, treating the map like a grid with an X, Y and Z axis.

2. The Galactic Sea

The etymology of “Galactic” comes from the same places as “lactos,” or “milk,” in that “Galaxy” is ultimately just the Latin translation of the Milky Way. This notion of the Galaxy as liquid is a fitting one, as is calling space “a sea,” not because it’s an exact fit, but because it highlights some important truths about the nature of a Galaxy and its stars: they are better thought of as a fluid than a solid.

Islands serve as a useful metaphor for stars because both involve enormous distances of inhospitable, flat desolation punctuated by a scattering of tiny, life supporting points, but islands and stars have at least one critical difference that I wish to highlight: islands do not move, but stars do. Stars orbitthe galactic center, and they do so at different speeds. This means that the constellations of our sky have changed and will continue to change, that what was once our nearest star will not be in the future, and that everything, given enough time, will dramatically change.

Now, a brief point about this: in 36,000 years, Ross 248 will come within 3 light years of the Solar system and thus be our closest star, and this will last about 8,000 years. Meanwhile, in 50,000 years, Niagra falls will have eroded away. So, we can overstate the fluidity of the galaxy. It shifts and changes, but so do mountains. Even if we look into the far distant future of 10,000 years from now, we’re unlikely to see much of a difference: the sorts of animations astronomers make of constellations changing tend to be on scales of 100,000+ years. The real point about this objection is that no star has a concerete “connection” to one another.

Allow me to draw a contrast between galactic “geography” and planetary geography. Imagine a continent with a great ocean on its western coast and a mountain range down its center, and this great continent stretches from the arctic to the equator. The moisture of the western ocean and the mountains at the center mean that the western half of the continent is likely moist and filled with rivers as the clouds that build up over the sea rain out over the western side of the mountains and flows back down into the ocean. This likely means that the eastern half of the continent is dry and arid, a desert. Meanwhile, the north is likely cold and the south is likely hot. One can walk from the cold north to the hot south and notice the temperature slowly increasing during his long, long trek. The continent’s parts relate to one another and are a smooth, continual set of cause-and-effect.

Not so with star systems. Imagine Tatooine, a hot and arid world. Do you imagine all the planets in the Tatooine system are hot? No, of course not. A world closer to its star(s) might be bitterly hot, while those more distant will be cooler and cooler. Presumably the system has asteroid belts and gas giants and kuiper belts. Just because Tatooine is hot has no bearing on the warmth, dryness or coldness of other worlds, other than that if Tatooine is in the habitable zone, other worlds probably aren’t. In Endless Space, the game claims that red stars are more likely to have “hot” worlds while blue stars are more likely to have “cold” stars, a useful conceit when deciding which stars to try to colonize, but as one poster pointed out, has no real bearing on the climate of worlds: one can easily have a hot world around a (technically hot) blue star and a cold world around a (technically cold) red star, or vice versa, because their orbital distancematters more than the temperature of the star.

Worse, no star is really going to impact another star. You’re never going to have a “belt” of “Iron stars” all with hot, volcanic worlds and asteroid belts, making it a place well known for industry. There’s no mechanism by which to create that sort of distinct, thematic image. Instead, all of your stars will be scattered and random, creating a homogenous mixture when taken as a whole. Even the arms of a galaxy might be an emergent property the orbits of a galaxy, creating a sort of wave by the sheer chance of bunching up at particular points (though the nature of galactic arms is still a matter of debate).

Without structure, we cannot point to a region of space, like a galactic arm and assign it a theme, because there’s no inherent connection between the stars there, other than the fact that, at this moment, they happen to be close to one another.

3. The Galaxy is Huge

Space is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space. –Douglas Adams, Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

The primary problem with a galactic map is that it’s too big. Think about how many Star Wars planets you can name. Using wikipedia, I get about160 with a very rough count. Astronomers can’t really pin down the number, but they estimate between 100 and 400 billionstars. Assuming one Star Wars world or moon worth discussing per star, rather than multiple planets and moons per star, the Star Wars galaxy details 0.0000000064% of the galaxy. More realistic games, like Traveler, have these enormous maps with empires so vast that even with FTL it might take a human lifetime to cross them, and they stillrepresent just a drop in the bucket of the whole of the galaxy.

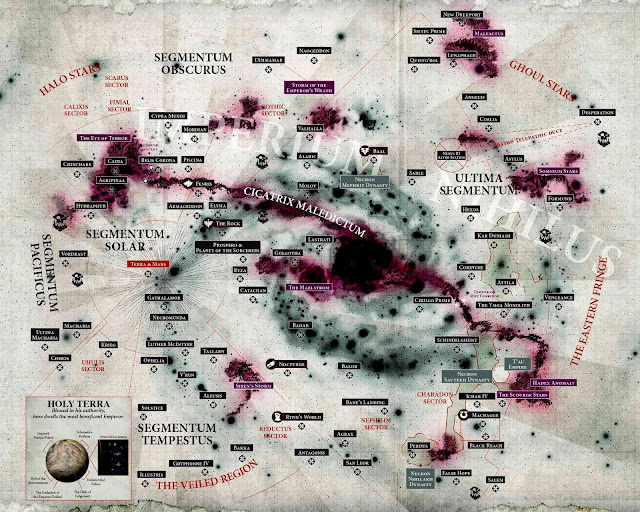

The only game to remotely get the scale of the galaxy right, and I still think they’re underselling it, is Warhammer 40k. It actually gets things like population numbers something close to right, because if you have a substantial fraction of those stars colonizes (say 1% of 100 billion stars, or 1 billion stars), and you have an average of 1 billion people gives you a quintillion people. It’s close to saying every person currently on planet earth got their own world of a billion people to rule. This is why only a fraction of the Imperium is capable of psychic power, and yet the imperium has no problem just shoveling psychics into (10,000 a day or so, if I remember correctly) the Astronomican to keep it powered, because that’s “only” about 10 million per year, and if only 1% of the population has the capacity to power the Astronomican, you still have literally trillions of people to choose from.

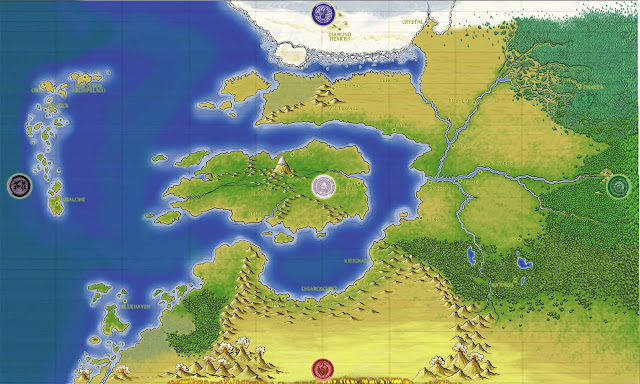

Warhammer 40k doesn’t bother to discuss structures, it just lays out a map of the galaxy and talks about general trends: “Here are the Gaunt Stars,” and “This little spot is the vast Tau Empire,” and so on. There are so many space marine chapters, which are the best of the best of the best, that you every player could make up their own and it probably wouldn’t detail every chapter in existence. You have plenty of room to drop your own whole set of worlds, and with vast and ancient history, and to have Chaos swallow them up like nothing without even making a marginal impact on the rest of the galaxy, a fact many a video game and Games Workshop themselves gleefully exploit.

Lying about Galactic Maps

So Star Wars is wrong, not just a little wrong, but really really wrong. Yet, nobody notices. Why? Because people aren’t astrophyscists and Star Wars doesn’t really concern itself with astrophysics.

Space Opera is famous for shrinking space down or just handwaving travel. A recent episode of Voltron had a planet so packed with explosives that, if detonated, would “destroy everything within a distance of 10 solar systems.” That either means within something like 1,000 AU, which is nothing (that might take out an oort cloud, but no other star systems), or it means that ten nearby systems would be destroyed, which means the explosive has the capacity to reach light years, which is a feat on par with a super-nova (and even those don’t destroy nearby systems, unless very very close, but it might sterilize them). But we don’t mind, for the same reason we don’t mind Han Solo stepping out of a door and watching the Republic capital-world, and other worlds being blown up by Starkiller Base (never mind the fact that it shot a multiple FTL beams). It’s similar to how many children’s cartoons will show comets, ringed planets, stars, asteroids and such all within hopping distance of one another. It just doesn’t matter, as long as you can maintain a thin veneer of reality.

Star Wars is really more concerned with changing planets the way one changes settings. They could as easily have stargates, except that would preclude the cool space battles. It doesn’t really matter if Naboo or Tatooine are closer to Coruscant, what matters is that we first want our story on Naboo, then on Tatooine, then on Coruscant. In this sense, a map doesn’t matter at all.

When it comes to spatial objects like black holes, pulsars, nebulae, asteroids or ringed worlds, most space opera simply sprinkle these into the background to justify weird things or to remind the viewer that he’s on an alien world. Perhaps a great ringed planet dominated the background of the ancient planet on which our characters adventure (a feature that has never been in Star Wars, for some reason!), or dead, volcanic world might be under the dour gaze of a “black sun,” a black hole surrounded by a nimbus of glowing gas giving it an otherworldly light.

This is why Star Wars doesn’t really have a map and, where it does, you don’t remember it: because it doesn’t matter. There are worlds, and you may well remember their names, but your characters will flit from world to world in a flash of onrushing, blue-shifted starlight. It’s an excuse, a conceit, and thus in principle, we don’t need a map.

That said, given that people don’t necessarily care that much about space opera galactic maps, we can lie, and we can make them however we want. Why? For the same reasons we make any map: inspiration, geopolitical realities, and beautiful obsfuscation.

Structure the Unstructured

“If the Galaxy has a bright center, Tatooine is the point farthest from it.” – Luke Skywalker, A New Hope

Despite the fact that we claimed a galaxy has no structure, it does have some structures we can exploit. Galaxies tend to be most densely populated (with stars) at their core, which tends to have a “bulge” that rises above and below the galactic plane. It also tends to be more densely populated in its arms than outside of them though, of course, there are stars everywhere.

Star Wars centralizes political power in the galactic core. There are some problems with this realistically speaking (the galactic core might be too energetic to support life in the long-term), but that hardly matters for our purposes. As one moves farther from that “bright center,” one begins to exceed the grasp of power and enters regions of increasing lawlessness where alien powers begin to dominate (that is, we’re reaching the exotic edges of the map).

Star Wars also describes regions, the most famous being the “unknown region.” Most of these are based on how the galaxy was explored and colonized: these are cultural regions rather than geographical ones (sort of like how we associate Egypt more with its ancient civilization than its desert terrain), though we have some “political” ones, like “Hutt Space,” a popular one especially in video games.

We can also use structures that do exist in galaxies, even if they don’t work quite the way we’ll use them. These include armsand clusters. An arm might be a united region of space, as it would legitimately be more densely packed with stars than the regions between arms, and we might use clusters to describe closely associated regions of stars. A cluster might plausibly share some astrophysical characteristics (they tend to be stars formed together, and thus might share similar metallicity and thus occurrence of asteroids or cold bodies) or similar age (and thus might all be protostars with nebulae or truly ancient stars with vanished civilizations), and would likely share cultural characteristics as a single civilization might have colonized all the stars of a particular cluster.

We can also create fictional structures using hyperspace. Star Wars uses hyperspace lanes, and I’ll borrow the concept of “Constellations” from the Endless Space series: certain stars are more easily reached via FTL by particular “routes” that are unique to the geography of whatever medium that makes FTL possible (in this case, hyperspace). Thus while nothing “connects” two stars in real space, in hyperspace they might have a very quick and easy connection and thus regularly interact, while other stars even closer to one another might have no such hyperspatial connection and thus have no similar causal connection as people will rarely travel between them.

Ignoring 99.9999999% of the Galaxy

But how can we justify going from ~200 billion stars to ~200 stars? We have 9 orders of magnitude less stars in Star Wars than in the actual galaxy. The obvious answer is that moststars aren’t worth talking about. The presumption in Star Wars is that there are far more stars than mentioned, hence why new films have no problem just dropping a new star system, like Takodana or Geonosis, or expanded universe works will happily conjure up homeworlds, like Ryloth, out of thin air. They couldbe there and given the sheer number of stars, nobody talks about all of them all the time.

We can easily say that few stars are easily reached via hyperspace. If only a fraction of stars in the galaxy are habitable, and only a fraction of that can be easily reached via hyperspace, than we might easily only have “thousands” of worlds worth discussing, rather than billions. Given our rapid speed of movement, the players will barely notice that their ships just travelled a thousand light years and byspassed a million stars to go from one interesting world to another interesting world given that the million worlds they bypassed aren’t interesting.

This does mean that, presumably, there are untold, epic amounts of real-estate just out there for grabs, for pirates, smugglers, and would-be colonists to just grab. It may well mean that most of the civilizations of the galaxy are “dark” and unheard of, never seen and never involved, unless something shifts the shape of hyperspace and a previously isolated world suddenly finds itself exposed to the vast might of an intragalactic civilization it had never even known existed and rapidly finds itself overwhelmed. To me, though, this is a feature, rather than a bug.

Having Fun with Astrophysics

I mentioned above that galaxies do have quite a few structures we can exploit. We have to lie a bit about how much they matter, but the average space opera player is generally going to be okay with interesting-but-inaccurate astrophysics, and if they’re not, if they want to talk about what’s “really” going to go on, well, as long interrupt your session, I think that’s fine, but I like talking about astronomy! I’m not trying to be accurate, and I’ll happily fess up to that. Instead, I want to find a way to invoke some of the fascination people have with space to create a sort of mythology around a location, to explain what makes it unique and what makes it stand out.

Stars vary a great deal in type, and we can exploit this to say a great deal about how unusual a star system is. Tatooine has two stars. Stars come in every color, from blue to red to yellow (though it should be noted that, realistically, all of them will look white). A bloated, red super-giant says “the end of the world” to many players. I’ve never seen a game set in a proto-system, but such a primordial world would certainly offer a spectactular view, with regular meteor showers, a nebulous night-sky and a blurred out star shining brightly and setting its planetary nebula a light. Similarly, a dying star that’s slowly sloughing off its exterior would create a magnificent view, though how a world would survive that remains an open question (Star Wars worlds have survived worse!). On the more intensely energetic side, we have neutron stars, pulsars, magnetars and, of course, black holes. These tend to be too powerful and too disastrous to have livable worlds around them, but they may shape entire local clusters, dominating their themes. Similarly, truly giant stars may well serve a similar roll to pulsars and black holes (typically, a super-giant star is just a black hole or neutron star waiting to happen), serving as the heavy center of a local cluster.

A star system can have interesting planets too. I find that space opera doesn’t concern itself overly much with any planets but the single one in a system the players care about, but they can offer some variety. It might be possible to have habitable worlds orbiting gas giants. A world with a mighty Jovian slowly rising over its horizon, or a majestic ringed giant in the distance can add a lot of character to a world. We might also set a station in orbit above a gas giant, mining it for whatever we wish. On the even heavier side, we might have a brown dwarf, a failed star that’s heavy enough to be exceedingly warm and perhaps even create some very minimal fusion, but not to fully ignite like a star. Asteroid belts aren’t planets, but are famous as locations for grizzled miners and interstellar hillfolk. Asteroids legitimately have considerable mineral wealth in them. We can also play with icy worlds or ice rings around worlds; the Old Republic has at least one space battle scene set amidst these great space-faring, crystalline ice-bergs!

A nebula is more impressive in space photography than in real life, but that doesn’t mean we can’t exploit the more cinematic version of them. In reality, a nebula only looks like a fog because over a scale of light yearsits mass begins to obscure some of our line of sight: it hasn’t got a fraction of the density of the air atop mount Everest, never mind the density of a fog bank. That doesn’t have to stop us from making improbably thick and stormy nebulae. And a nebula can legitimately cover many, many light years, which means if we give it cinematic properties, it can create a “dark sector” all of which poses navigational hazards and may hide pirates!

Telling a Story with Astrophysics

We don’t have meaningful interstellar structures in a geographicalsense when it comes to galactic maps, but that doesn’t mean we can’t fudge things. Better, while there’s no logical reason for the worlds of a swathe of space to share a particular trait, there’s no reason they couldn’t either. In a sense, we’re free to tell whatever story we want, within the limits of suspension of disbelief, about any part of the map.

For example, earlier I said that there’s no real reason to have an “iron belt” of worlds all rich in metals and hot, like a forge, but there’s also no reason we couldn’t. Perhaps we have a cluster of very high metallicity stars that formed recently. At the heart of this cluster there resides an enormous red super-giant, which looms over every world in the cluster like this great, baleful red eye. The cluster might have a star system rich in asteroids, and another star system with a metal-rich, volcanic planet, and a third star system with this huge, coal-black “Hot jupiter” that hovers close enough to its parent star to be impressive, but not so close that we can’t mine it (perhaps it’s rich in star-fuel). Immediately, we have a theme of “iron stars,” several star systems rich in mineral wealth and likely poor in everything else.. We might imagine the denizens of these worlds to be gritty miners and soot-covered thieves and vast industrial complexes ruled by sallow-cheeked corporate lords.

We might contrast such a region of space with a glimmering, rainbow-sheened nebula lit from within by several stars being born. We might have a garden planet in one system and a crystal-ice planet with silvery rings in another. Clearly, this is region of space where princesses and knights come from, with brilliant castles and sacred spaces. We can see a difference between these worlds and the “iron” worlds.

Are these regions of space “realistic?” Maybe not, but they might inspire you, and they’re easily differentiated and easily understood. For a space opera setting, that may well be enough!