I’m afraid I can’t find the quote by Kenneth Hite, but it amounts to this: No matter how creative you are, the real world will come up with something stranger and cooler than you can ever come up with, and you’d thus be a fool not to pillage history.

This is especially important for Psi-Wars, for two reasons. First, Star Wars, from which Psi-Wars draws is principle inspiration, is very thoroughly based on history, especially the History Channel favorites like World War 2 and the Roman Empire. If we want Psi-Wars to feel the same, then we need to draw our inspiration from a similar source. But more importantly, Psi-Wars must necessarily be larger than Star Wars, given that Star Wars is “only” a movie, while Psi-Wars needs to be a setting that supports a huge variety of different possible games. That means we need more material to steal from, and there’s hardly more material than all of human history.

As before, though, I intend to pursue emulation rather than imitation. I don’t want Psi-Wars to be the the Fall of the Roman Republic with the serial numbers scratched off, I want to understand what made Rome fall, and then draw parallels with that with the fall of my Galactic Empire. This is the same thing Lucas did in the prequels though I’m quite sure I’ll draw different historical conclusions than he did (It takes more than a single war to turn a democracy into a dictatorship). We need to do our homework, and I certainly have (Look, I like history, okay!), and I’ve noted some sources below. Those are just some sources, a place where you might start. The point here is hunting for ideas, not necessarily a rigorous historical thesis, thus I’ve happily included semi-fictional works and well-researched RPGs. It’s not meant as an exhaustive bibliography of books I’ve gone through.

So, what part of history can I draw on for inspiration for Psi-Wars?

All of it.

Rome

|

| Gladiator, from Wikipedia |

- Dan Carlin’s Death Throes of the Roman Republic.

- the Gracchi Brothers from Extra Credit: History

- The History of Rome Podcast

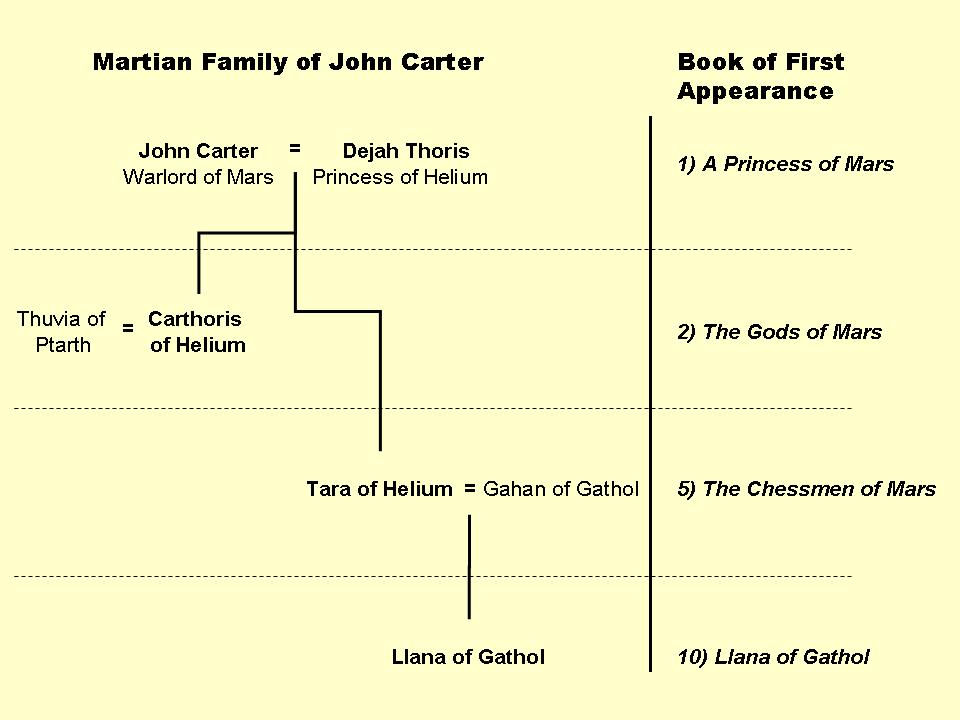

Star Wars clearly draws a lot of its inspiration from the Rise and Fall of the Roman Republic. Here, too, the Republic (with its Senate) is overthrown in a time of crisis by a man who becomes Emperor, only to face a civil war from his rivals, while barbaric (alien) threats press in on the civilized core. The rightful order of the world is on threat from all sides, and the Emperor destroys the Republic to save it.

And, really, why wouldn’t Star Wars draw inspiration from this rich source? Rome is nearly as far back as you can go and still run into, as Dan Carlin puts it, “full color history,” where we have a pretty good picture from the records of what’s going on. Suddenly, a strange and alien culture springs up that’s utterly unlike our own, and yet still so recognizably human. If their democracy could fall, then surely so can ours. George Lucas clearly wanted us to pay attention to that danger.

An empire is defined as “an aggregate of nations or people ruled over by an emperor or other powerful sovereign or government, usually a territory of greater extent than a kingdom

–Wikipedia

The change-over didn’t happen all once either. Every school kid knows about Julius Caesar, but he was never Emperor. His adopted son, Augustus Caesar, was the first Roman Emperor. Instead, what we see are long serious of events where to increasingly entrenched and violent sides come to blows, and when they kill Caesar (a hero to all of Rome!), that was a bridge too far, and then when Augustus Caesar wins, it’s clear to him that the only way to end the cycles of violence is to clamp down with an iron fist.

And the “rebellion” wasn’t nearly as clear cut as we see in Star Wars. Instead, we see the Republic vs Imperial side, of course, but then once the Imperial side wins, that side devolves into a horrid conflict between the victorious triumvirate until Augustus Caesar is the last man standing. This, by the way, is surprisingly typical for uprisings of this sort. Moreover, the “liberty loving side” was largely aristocratic. The war for the soul of Rome was fought by those who stood for the constitution, the aristocratic, land-owning, slave-holding elites, vs the dictatorial populist demagogues. The land owning class had gained enormous wealth and power during the rise of Rome, and didn’t want to share it with the increasingly impoverished common man, and one of the core justifications of the various power-grabs during this era was to better the lot of the common man. This rather puts a new spin on the rebellion being led by a Princess, doesn’t it?

In Star Wars, Palpatine definitely rises to power on the back of a war, as did the various populist Tribunes of Rome, but in Rome, the wars were of conquest and genocide or, more occasionally, in defense of the Republic against vast barbarian incursions. Desperately frightened Romans would give more and more power to their best and brightest, who would turn around and impose some serious reform that would incense one side of the other and, especially if they were making reforms that benefited the people, resulted in their assassination.

If we borrow some of this for Psi-Wars, what alien menace represents our barbaric incursions that our heroic would-be Emperor can gain fame standing against? Who are the aristocrats that stand for “the constitution” of the current Galactic Republic? How does this Emperor die, and who rises in his place? And how does that particular civil war play out? We have the aristocratic side, but if they’re largely defeated, does the Empire have to deal with other, upstart imperials from the alliance-from-hell that they made to take control of the empire?

And what fundamentally changed the fabric of the Republic so completely to allow this?

- Mithradates VI, the Poison King

- The Cimbri and the Battle of Vercellae

- The Marian Reforms, which shift the loyalty of Rome’s legions to her generals.

- The Social War

- The Catiline Conspiracy

World War 2

|

| from “Meet the Men who Hunt Nazis,” the Telegraph |

Sources:

- Third Reich – Rise

- Nazi Occult by Kenneth Hite

- The Interwar Period and its Impact on the World with a Focus on Germany

- Dan Carlin’s Ghosts of the Ostfront

If Star Wars is the story of how democracies fall and how they can be restored, I must admit that I find most discussions of the rise of Nazi Germany frustrating, as they seldom get into the root causes. Instead, Hitler inexplicably rises to power thanks to fear and his magical, hypnotic powers, which matches how Star Wars treats it. Personally, I found Hite’s discussions of the origins of the Volkish movement and its connections to German nationalism enlightening, as well as the Interwar Period’s discussion of the delicate balancing act the Weimar republic was forced to make, including its evident external focus and unwillingness to violate treaties the German people found increasingly inexcusable. Thus, the rise of the Nazi party has more to do with economic hardship and a defiant wish for Germany to “take its rightful place” with the other European empires (the fact they were empires is sometimes forgotten in these discussions), as well as willingness to be “unapologetically German” in the sense that there seemed a general sense that being “unapologetically German” was controversial (perhaps because it was!). You can also find a strong element of propaganda and secret police inside the Nazi party from the very beginning: one reason Hitler was able to rise to power was that as soon as he had any power, he used it to dramatically suppress dissent.

Thus, in Psi-Wars, what sort of economic hardships and politically incorrect ideas begin to give rise to the rise of the Empire? What sort of secret police does the Emperor deploy to enforce his will upon the people and thus end the Galactic Republic?

Star Wars also borrows heavily from the imagery of World War 2, with great capital ships acting as carriers and battleships, while starfighters act as fighter. Stormtroopers draw their inspiration from German storm troopers, the AT-AT from the German Tiger, and so on. The Galactic Civil War of Star Wars is fought very much like World War 2, only “in space.”

But the politics of the war is completely different. In Star Wars, the only two powers are the Empire and the Rebellion, which isn’t a foreign power at all. This is an internal conflict. In World War 2, of course, Germany allied with other powers (Italy and Japan) to form the Axis, and the Allies included freedom-loving British (including aristocrats and a commonwealth that contained colonized nations, like India) and America, as well as the decidedly unfree Russia. If we draw the parallel further, who takes on these roles? The idea of an aristocracy fighting to hold onto their old privilege matches nicely with the parallel for the Roman civil war, but how do we represent America? Are they heroic minute-men or grasping, corporate industrialists with imperial ambitions of their own, or both? And what could stand in for Russia in the most brutal part of the war? If communism represents the rise of a virtually enslaved labor class against their oppressors, then what if the role of Russia in Psi-Wars is an area of space where robots have overthrown their masters and seek to persuade other robots to join them in their revolution? And what represents Japan or Italy? Does some ancient and mDan Carlin’s Wrath of the Khansystical culture join forces with the industrial might of the galactic core? Or perhaps this is best represented by a fusion between a splinter sect of our not-Jedi-Order joining forces with the Empire?

The Germans sought to cleanse the world of Jews, but they had some rather specific reasons. Setting aside centuries of racial mistrust of the Jews, conspiracy theories often center on banking and Nazi Germany was no different. Germans held people like the Rotschilds responsible for their downfall after WW1 (and you can find this sort of conspiracy making the rounds every few years to this day). We might draw from this a quiet (alien?) consortium of bankers, lenders and/or technologists who quietly empower people from behind the scenes (the “banking clans” of Clone Wars). Alternatively, the Jews might represent the Jedi, hunted to the brink of extinction by the Empire… or perhaps they represented by alien races who are being purged by a human Empire that wants to remain “pure.”

Fascinatingly, the lethal super-weapon of WW2 wasn’t acquired by the Nazis, but by the allies. What happens in a setting where the Rebel Alliance is the one that acquires the Death Star and uses it as a last ditch effort to kill literally billions by blowing major Imperial worlds? What sort of tone does that set?

Some additional interesting characters or ideas:

Sengoku Jidai and the Edo Era

|

| Total War Shogun 2 Wallpaper |

Sources:

- GURPS Japan

- the Sengoku Jidai from Extra Credit: History

- In the Name of the Buddha: the Rise and Fall of the Ikko Ikki, History of Japan podcast

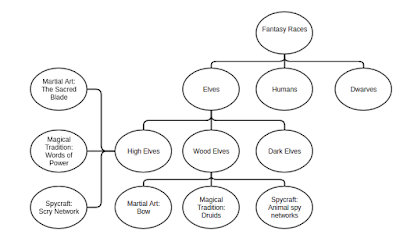

Using Japan as inspiration becomes difficult, because while the mood of a chambara film definitely comes across in Star Wars (at least the original trilogy), the history far less so. When we discuss Japanese history in regards to the samurai, two eras generally spring to mind. The first is the Sengoku Jidai, the warring era, where the Ashikaga Shogunate collapsed and various regional daimyos sprang up and vied for power until, at last, Tokugawa declared himself Shogun. This is the era that features samurai in armor and on horseback, cutting one another down and dying for their daimyo. It’s also the era that features ninjas.

If we borrow from this for Psi-Wars, interesting things emerge. If space knights are samurai, then this war is fought with space knights! And the emperor is a ceremonial position by this point, a religious figure head and a rallying figure dominated by the shogun. Each daimyo becomes the lord of a specific world, or a master of a few worlds. This, in short, looks nothing like Star Wars… but interesting nonetheless!

The second major era that springs to mind is the one most commonly featured in the “Jidaigeki” so beloved by George Lucas, is the Edo era, long after the Tokugawa shogunate has established its dominance. Now, the samurai has devolved back to his roots as bureaucrat and often enjoys a ceremonial position so long as his master continues to receive a stipend from the Shogunate. This is the era of the kimono-clad samurai who uses his fast-draw technique in a sudden duel, where the man to first draw his blade wins. It’s also the era of the geisha, where whores play at being ladies for the amusement of their largely fallen samurai customers who try to pretend to be more genteel than they really are, while gamblers and yakuza thugs similarly pretend to be classier than they are, and the lines between “noble” and “commoner” begin to slowly blur. It’s a somber and often sad era, not entirely applicable to the great galactic war… but the mood certain fits a galaxy whose best, most energetic days are behind it, which yearns to return to that golden age of yesteryear, even as time draws it relentlessly forward into a new and strange era.

Interesting Ideas

Romance of the Three Kingdoms and the Mandate of Heaven

- The Warring States period (If you want a quick, gamer-friendly take on it, look up Qin: the Warring States, and try the film Hero)

- Romance of the Three Kingdoms (If you need a more approachable version, try the Ravages of Time or, of course, the Dynasty Warriors video game series, also consider the fantastic Red Cliff. See if you can get it uncut)

- Weapons of the Gods

- Wrath of the Khans

Additional Characters and Ideas

- Cao Cao

- The treacherous Sima Yi

- Dong Zhuo

- Lu Bu

- Sun Quan and the Sun Family

- The virtuous Liu Bei

- The brilliant Zhuge Liang

- The history and mythology of the Shaolin temple, especially the five Shaolin masters

- The effectiveness and ruthlessness of Qin Shi Huang.

Medieval Europe and the Templars

- GURPS Crusades

- Knights Templar by Graeme Davis. See also:

- Templars: the Fighting Priests (Pyramid #3-19)

- The Knights Templar (Pyramid #3-86)

- Knights Templar: Separating Myth from History, by Real Crusader History

- The Council of Troyes, by Templar History

I must emphasize caution when exploring the templars as they represent both a very familiar history and a very strange, mysterious history, as conspiracies and magical thinking shrouds templar history in a veil of mystery and controversy. However, we can grab whatever crazed conspiracy theories we want, and mix familiar medieval history with other histories (the rise of the Ikko Ikki, the fall of the Shaolin temple) to create something new and unique.

Antiquity

|

| The Fire of Troy |